Preparing Mobile Home Park Residents for Wildfire in Lake County, Colorado

Publication Date: 2024

Abstract

This study explores wildfire risk and preparedness among mobile home park residents in Leadville, Colorado—a town of 2,633 residents within the wildland-urban interface (WUI) of Lake County, Colorado, a region at increasingly high risk for wildfire. Residents in mobile home parks are socially vulnerable to disasters and their manufactured homes are highly susceptible to fire. Although mobile home parks are a critical form of affordable housing, their wildfire risk and their residents’ preparedness for wildfires are understudied. This multi-methods project—conducted in partnership with Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue—was designed to address that gap. It involved two primary research activities: First, we used secondary parcel assessment data to identify wildfire risk on mobile home properties in Leadville. Second, we surveyed mobile home residents to identify their wildfire risk mitigation and preparedness needs. Results from the rapid wildfire risk assessments provide clear evidence that mobile home park residences are uniquely vulnerable to wildfire, both due to physical characteristics that are immutable, as well as characteristics that can be addressed through mitigation actions. However, since some of the characteristics driving high wildfire risk to mobile home park communities are either difficult or impossible to change, evacuation preparedness is of heightened importance for mobile home park residents. Respondents reported that mitigation and preparedness information tailored to their homes and residential sites, as well as financial assistance and combustible material disposal options, would help them attain mitigation and preparedness goals.

Introduction

In the western United States, the increasing probability of extreme wildfire (Balshi et al., 20091; Litschert et al., 20122; Westerling et al., 20063) and development of the wildland-urban interface (WUI) have resulted in a well-recognized problem: wildfire risk to WUI communities (e.g., Theobald & Romme, 20074; Gill & Stephens, 2009 5; Schoennagel et al., 20176). This project focuses on WUI areas within Lake County, Colorado, and is an extension of a project referred to hereafter as the “Lake County Wildfire Study”—a research collaboration between investigators and practitioners at the University of Colorado Boulder, the Wildfire Research Center, the Leadville/Lake Country Fire-Rescue, the Arkansas River Watershed Collaborative, and the Colorado State Forest Service. The Lake County Wildfire Study assessed wildfire risk on 930 properties, including 259 mobile home residences, and surveyed 683 residents about wildfire preparedness, mitigation, and risk communication. During this study, our project partners voiced elevated concerns about the wildfire vulnerability of the three mobile home parks in the study area, expressing that understanding and bolstering wildfire evacuation preparedness in these communities was a high priority. The response rate for the study was 23%, however, we received only one survey response—which was incomplete—from a mobile home park resident. The “Mobile Home Park Wildfire Study” presented in this report arose from recognition that we could not adequately answer our partners’ questions about mobile home residents’ preparedness and mitigation needs without further data collection efforts.

Mobile home parks have a type of land tenure in which residents rent or own manufactured homes that are located on property typically owned by landlords, or sometimes cooperatively owned by residents (Durst & Sullivan, 20197). Manufactured homes are built in factories and assembled elsewhere on a trailer chassis, rather than a permanent foundation (Durst & Sullivan, 2019). Since 1976, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has described this housing type as “manufactured” rather than “mobile” homes to denote their lack of mobility; however, we refer to this housing type as “mobile home parks” to reflect the official names of the three parks in this study. A 2018 assessment of Lake County housing needs identified 16% of Lake County’s housing stock as manufactured houses in mobile home parks (Economic & Planning Systems, Inc., 20188). The Mobile Home Park Wildfire Study included three mobile home parks, located next to U.S. Highway 24 on the sparsely populated outskirts of Leadville in Lake County: Mountain Valley Estates and Mountain View Village East and West. These mobile home parks are at high risk of wildfire due to the proximity of public lands, the frequency of high winds, and limited local emergency response capacity.

Due to their relative affordability, mobile home parks often house residents of lower socioeconomic status. Reflecting this trend, the Environmental Protection Agency’s (n.d.9) EJScreen tool identifies the northern Leadville area as extremely vulnerable socioeconomically and environmentally due to several factors; these include a high percentage of low-income residents, residents with less than high school education, and limited English-speaking households, as well as proximity to a superfund site. In the U.S. Census Bureau’s Leadville North Census County Division, 67% of residents reported children under 18 years of age (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020a10), and the median age was 32 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020b11). Furthermore, 71% of the population identified as “Hispanic or Latino” (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020a), and 24% of the population in the Leadville North Census County Division reported speaking English “not well” or “not at all” (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020b). Additionally, 22% of families had incomes below the poverty line and 36% of residents were unemployed (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020b). Almost half (45%) of residents reported working in the construction industry, commuting an average of 25 minutes by car to work (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020b). Our Lake County partners explained that many mobile home residents primarily speak Spanish, may be undocumented, and are less connected to the fire department. These socioeconomic factors may inhibit residents’ ability to prepare for, respond to, and recover from wildfire. Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue has only recently begun forming connections with residents, via a smoke detector outreach program, spearheaded by the Lake County Fire Marshall.

Mobile home parks face unique wildfire risk mitigation challenges. First, these residences are particularly susceptible to home-to-home transmission of wildfire due to the density of homes, as each home may serve as an ignition source. Second, land tenure can obstruct mitigation action. For example, the proximity of vegetation and non-vegetative combustibles to the home are two important property characteristics that may influence the likelihood of home ignition and structural loss. While mobile home residents may mitigate risk from non-vegetative combustibles (e.g., removing propane tanks, outdoor furniture), their lack of land ownership affords them less control over risk factors beyond their homes, such as proximity to vegetation, relying instead on management by mobile home park owners. The three mobile home parks in our study are managed by out-of-state property owners, which may influence responsiveness to maintenance requests, as has been the case with maintenance of emergency access roads (Economic & Planning Systems, Inc., 2018). Furthermore, according to our Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue partners, the owners of the mobile home parks change frequently, inhibiting the fire department’s ability to educate mobile home park owners about wildfire risk. Given the unique socioeconomic and physical vulnerability of mobile home park residents to wildfire, as well as potential limitations on risk mitigation, it is especially critical to support wildfire evacuation preparedness activities as a central component of community wildfire readiness.

Despite importance of mobile home parks in the WUI as an affordable housing option, there is limited research on wildfire risk to this community type or how to address residents’ risk mitigation and preparedness needs (Collins & Bolin, 200912; Pierce et al., 202213). To address this gap, the research team analyzed pre-existing parcel-level wildfire risk data and gathered household survey data from 33 residents of three mobile home parks in Lake County, Colorado. Our purpose was threefold:

- Identify unique physical wildfire risks to mobile home parks and opportunities to mitigate those risks,

- Identify Lake County mobile home park residents’ wildfire risk perceptions and risk communication preferences, evacuation preparedness needs, and barriers to and incentives for mitigation action, and

- Share outreach and policy recommendations with our Lake County partners.

Literature Review

Wildfire Risk Mitigation and Preparedness

Many factors shape wildfire risk at the parcel level, from building materials and home ignition potential to defensible space, background conditions, and ease of property access (Meldrum et al. 202214; Meldrum et al., 201815; Caton et al., 201716; Hakes et al., 201717; Quarles et al., 201018). Residents can respond to wildfire risk by implementing mitigation measures around the home and bolstering evacuation preparedness. Wildfire preparedness includes identifying evacuation routes, signing up for emergency notifications, gathering supplies, and developing an evacuation plan with family members; see, for example, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Wildfire Ready website for a list of recommended preparedness steps. Mitigating wildfire risk factors include tasks that residents can accomplish more easily (e.g., removing combustible items from around the home) and tasks that are more expensive (e.g., modifying landscaping, changing building materials) or out of residents’ control (e.g., distance to dangerous topography that could exacerbate wildfire behavior). Residents and communities can differ in their capacity to address such vulnerabilities, both individually and communally (Grajdura et al., 202119; Meldrum et al., 2018; Paveglio et al., 201520). At the individual level, Grajdura et al. (2021) found that age, race, income, smartphone ownership, and presence of community evacuation planning influenced wildfire evacuations for the 2018 Camp Fire in California. At the neighborhood level, Warziniack et al. (201921) found that homeowners who had completed mitigation tended to cluster together, as did homeowners who had not completed mitigation, suggesting that neighbors may influence each other’s mitigation actions. At the community level, Paveglio et al. (2015) noted that community characteristics, such as financial resources and social structures, may facilitate or inhibit mitigation action. Community organizations hoping to prepare residents for wildfire must assess the variable capacities and needs of their residents.

Vulnerability to Hazards Among Mobile Home Park Residents

Empirical research on mobile home parks and their vulnerability to wildfire is limited (Durst & Sullivan, 2019; Sullivan, 201822). Research focused on Californian mobile home parks highlighted greater exposure to wildfire in mobile home parks compared to other housing types (Pierce et al., 2022), and analysis the 2018 Camp Fire (McConnell & Braneon, 202423) found greater levels of home destruction among this housing type. In addition to wildfire exposure, mobile home park residents may face unique barriers to mitigating risk and preparing for wildfire. First, because mobile home park residents often rent their home, the land underneath it, or both (Durst & Sullivan, 2019), renter restrictions may limit mitigation action. Second, residents may have limited financial resources and may not be able to take advantage of community wildfire mitigation programs. For example, Meldrum and colleagues (202424) that a cost-share program in western Colorado, which had been designed to decrease financial barriers to vegetation management, was more likely to benefit higher-income residents who were better able to pay their portion of the cost. Third, residents in our study area whose primary language is not English—or those who are undocumented and thus wary of interactions with government officials—may have less access to or awareness of community mitigation programs. These same socioeconomic factors may also affect evacuation preparedness. National analysis of American Community Survey data found that manufactured housing residents in California had fewer financial resources, less internet information access, and more difficulty securing alternate housing post-fire than other household types—evidence which suggests possible impacts on the ability of these residents to prepare for wildfire (Pierce et al., 2022). Further research on how community organizations can support mobile home residents in their wildfire mitigation and preparedness efforts may help address these barriers.

Mobile home residents may also be particularly vulnerable during and after wildfires. Analysis of neighborhood change following the 2018 Camp Fire in California (McConnell & Braneon, 2024) found that mobile home residents were significantly more likely to be destroyed in the wildfire and lower-income or renter-occupied residences were rebuilt more slowly. Research on mobile home vulnerability to flooding also sheds light on post-disaster recovery among mobile home parks. Smith et al. (202225) noted that mobile home park residents may receive less support from disaster relief programs; furthermore, they are often vulnerable to post-disaster eviction. Given these post-disaster vulnerabilities, wildfire risk mitigation and preparedness are especially important.

Wildfire Risk Communication Preferences Among Wildland Urban Interface Residents

Within the ever-changing landscape of social media and the internet, the ways in which individuals receive information have grown increasingly complex, deepening the importance of understanding communication preferences. Understanding how residents prefer to receive information about wildfire risk can help community organizations design programs that better reach residents. Residents may prefer different sources of information (e.g., the local fire department, friends and family, or a homeowners’ association) as well as different channels of communication (e.g., radio, one-on-one conversations, newsletters). Past research points toward the importance of local and personalized channels and sources of wildfire risk information. McCaffrey and colleagues (200426) found that residents in Incline Village, Nevada, were more likely to be aware of wildfire information from less tailored information channels (e.g., newspapers, TV), but information channels perceived as more personalized (e.g., personal contacts, community meetings) were more effective in encouraging risk mitigation behaviors. Brenkert-Smith et al. (201327) highlighted that residents who interacted with local and fire-specific sources of information had greater awareness of wildfire risk, an important precursor to mitigation action. In a cross-community analysis, Meldrum et al. (2018) found that resident wildfire risk communication preferences varied not just between individuals, but between communities. While this research provides insights into residential wildfire risk communication, it does not capture more recent channels of communication, nor does it provide insight into the communication needs of mobile home park residents.

Co-Productive Social Science and the WiRē Approach

This project was designed in the spirit of the WiRē Approach (pronounced “wy-ree, which is a collaborative, co-productive form of research”) (Wildfire Research, n.d.-a28). Coproduction is a research method characterized by the deeper involvement of information users and other stakeholders in the research process, such that research products better serve those users (Bamzai-Dodson et al., 202129, 2012]); Meadow et al., 2015). Our research team has developed the WiRē Approach over nearly two decades with the goal of providing actionable information that helps local fire organizations across the United States to understand and prepare their residents for wildfire (Champ et al., 202230). We have found that individual- and community-scale data is most actionable for local fire organizations because that is the scale at which they are operating. WiRē efforts have resulted in over 20,000 parcel risk assessments and 8,000 household survey responses across 23 projects ranging in scale from individual neighborhoods within a city to multiple fire districts across a county (e.g., Brenkert-Smith et al., 202331; Goolsby et al., 202332; Wildfire Research, n.d.-b33). However, prior to research efforts in Lake County, the WiRē Approach had only been implemented in one Washington state project area that included a mobile home park. That effort, while yielding high survey response rates ranging from 33% to 71% in the other communities within the Washington state study area (Brenkert-Smith et al., 202034), yielded no responses from the mobile home park. This research experience informed our research efforts in Lake County.

Research Questions

This study was designed to identify opportunities for Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue to encourage wildfire risk mitigation and preparedness amongst mobile home park residents. More specifically, we answered these five questions:

- How is parcel-level wildfire risk similar or different between mobile home and non-mobile home housing?

- How do mobile home park residents perceive wildfire risk to their homes?

- To what extent are mobile home park residents prepared to evacuate in the event of wildfire?

- How do mobile home park residents prefer to receive wildfire risk information?

- What prevents mobile home park residents from mitigating, and what might encourage them to do so?

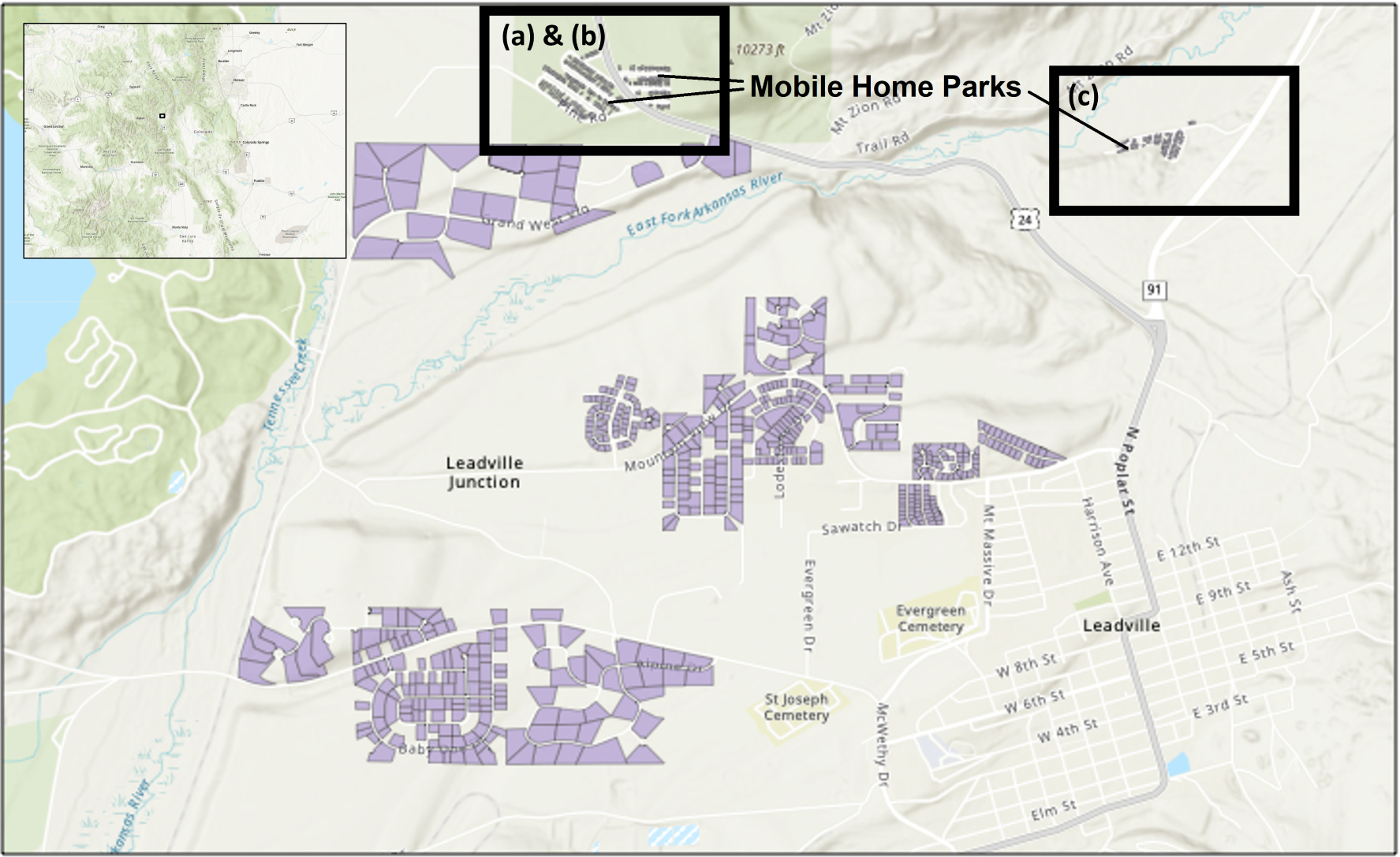

Research Design

This mixed method research study involved two primary research activities: First, we conducted a comparative analysis of wildfire risk in mobile homes and non-mobile homes using secondary data from the original “Lake County Wildfire Study.” Second, we shortened the Lake County Wildfire Study survey instrument and tailored it to the context of mobile home parks. The Mobile Home Park Wildfire Survey was distributed to all mobile home households in the study area of the Lake County Wildfire Study, using a targeted recruitment approach to increase participation among this hard-to-reach population (see mobile home parks identified as insets a, b, and c in Figure 1). Table 1 shows the data that we collected and analyzed for this study. We explain each of these data collection methods in more detail below, after providing an overview of the Lake County Wildfire Study and our research partnership.

Figure 1. Mobile Home Park Wildfire Study Area

Note. Map produced by the Wildfire Research Center. Map highlights the three mobile home parks in the study area, Mountain View Village East (a), Mountain View Village West (b), and Mountain Valley Estates (c), in the context of the Lake County Wildfire Study. Purple shading indicates the residential parcels where rapid wildfire risk assessments were conducted.

Table 1. Mobile Home Park Data Collection: Parcel Risk Assessments and Resident Surveys

(n) |

(n) |

(n) |

(%) |

(%) |

(%) |

|

Note. The initials "na" refer to not applicable. a Refers to the percentage of completed surveys in English. b Refers to the percentage of completed surveys in Spanish. c Assessors missed 2 parcels in Mountain View Village West during parcel-level rapid wildfire risk assessments.

The Lake County Wildfire Study

The goal of the Lake County Wildfire Study, which preceded the Mobile Home Park Wildfire Study, was to better understand wildfire risk and homeowner perspectives in Lake County (see study area in illustrated Figure 1 above). Our local project partners (refer to “Research Partners” below) selected the study area communities near Leadville, Colorado, based on what would be most useful to their programs, including detached, single-family residential parcels and the manufactured homes in three mobile home parks. The Lake County Wildfire Study involved two types of data collection: (1) rapid wildfire risk assessments of all residential parcels in the study area and (2) a 16-page survey sent to owners of the assessed parcels. The mailing list was pulled from the County Assessor’s Office records, and thus limited to owner addresses. Unfortunately, approximately 33% of the initial letters sent to mobile home park properties announcing the launch of the Lake County Wildfire Study were systematically returned marked “undeliverable.” Letters were undeliverable for a number of reasons including errors in the County Assessor database, lack of mail receptacles, vacant properties, and property owners owning multiple rental structures within the mobile home parks. As noted previously, among the successfully delivered household surveys, there was only one survey returned by a mobile home park resident and it was partially completed. As such, the research team sought a FEMA Quick Response Grant to extend research efforts.

Research Partners

The research team had established collaborative relationships with local partners due to the Lake County Wildfire Study. In particular, our main project partner, the Colorado State Forest Service—Salida Field Office, introduced us to the Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue Fire Chief and Fire Marshall, who provided critical insights into how mobile home park residents might best prepare for wildfire and what survey information would best support their outreach and programmatic efforts. The Fire Marshall, coauthor Steve Boyle, had established rapport with residents in the three mobile home park sites during previous efforts to install residential smoke detectors, providing increased access to the study area. The Fire Marshall provided insights into the sociocultural context of the mobile home parks, including the importance of providing correspondence and survey instruments in both English and Spanish.

Comparative Analysis of Mobile Home Park and Single-Family Home Parcel Risk Data

Parcel-Level Rapid Wildfire Risk Assessment Secondary Data

We used the parcel risk assessment data (N=777) from the Lake County Wildfire Study to compare wildfire risk on mobile home (n=259) and non-mobile home parcels (n=518). Risk assessments were conducted as a census of all residential parcels in high priority areas, as identified by the Colorado State Forest Service and Lake County Fire Rescue. Figure 1 highlights the residential parcels where rapid assessments were conducted. During the rapid assessment, each residential parcel was evaluated based on 13 risk attributes, grouped into four categories: home ignition potential (e.g., building materials), defensible space (i.e., distance from home to combustible materials including vegetation), background conditions (e.g., topography), and property access (e.g., driveway clearance and egress routes). The risk assessment has been developed during a decade of collaborative efforts between the researchers and wildfire mitigation experts. It is rooted in the foundational literature on the home ignition zone and is consistent with the National Fire Protection Association 1144 Standard for Reducing Structure Ignition Hazards from Wildland Fire (Cohen, 201935; National Fire Protection Association, 201836). The attributes that comprise the risk assessment are weighted based on their relative contribution to likelihood of home ignition and when combined provide an overall risk score for each property. The risk scores are binned into five categories: low (20-250), moderate (251-325), high (326-455), very high (456-540), and extreme (541-1000) wildfire risk. A full discussion of the methods used to assess the 13 risk attributes, as well as overall risk, can be found in Brenkert-Smith et al., 2023, as well as on the Wildfire Research Center's WiRē Rapid Assessment Scoring Guide (202337). A demonstration of the relationship between the attributes and wildfire outcomes can be found in Meldrum et al. 2022.

Comparative Analysis of Parcel-Level Wildfire Risk

Using all data collected in the Lake County Wildfire Study, the research team compared rapid wildfire risk assessments of 259 mobile home park parcels and 518 non-mobile home park parcels (i.e., all other assessed residential parcels in the Lake County Wildfire Study). We compared the distribution of risk ratings for each risk attribute, reporting initial descriptive statistics (e.g., percentage of parcels) below. The research team has plans to perform further statistical comparisons as a next step in the research process.

Mobile Home Park Wildfire Survey

Collaborative Survey Design

We collaborated with our Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue partners to design the Mobile Home Park Wildfire Survey data collection effort. First, our partners contributed to selecting a subset of the Lake County Wildfire Study’s 16 pages of survey questions (the Lake County Wildfire Study survey can be found in Appendix A). We chose a 3-page survey length, both to minimize the time burden of responding to the survey and to adhere to the project’s printing budget. We relied on our partners to identify survey questions that could actionably inform their outreach and programs. For example, although the Lake County Wildfire Survey devotes substantial questions to wildfire risk reduction activities, the Mobile Home Park Wildfire Survey focused mostly on wildfire evacuation preparedness. Our partners believed evacuation preparedness was the more important set of behaviors to focus on with their mobile home park constituents, because it can be difficult for residents in this community type to adequately mitigate wildfire risk.

Our partners also provided preliminary insights into the background and demographics of residents, including the large population of primarily Spanish-speaking residents, and the presence of undocumented residents. Our partners noted that residents could be cautious about filling out surveys or sharing personal information. This informed our decision not to include demographic questions in the survey, nor to collect personal identifying information such as residents’ addresses, as we did in the Lake County Wildfire Study. The survey page limit, and our partners’ advice on what information would be most actionable for their programs, also factored into the decision. That said, we did track responses by mobile home park, such that our partners could compare the problems and needs of the three mobile home parks when tailoring programs and outreach.

Survey Measures

The survey included questions about current wildfire evacuation preparedness planning; wildfire risk perception; wildfire risk information source and channel preferences; and barriers and incentives to taking action to mitigate wildfire risk. These questions were selected from a larger set of questions on the Lake County Wildfire Survey, such that survey results could be compared between the two research efforts. We adapted some of the survey questions from the Lake County Wildfire Survey with language that was more appropriate for mobile home residents. For example, because many mobile home park residents often do not own the land upon which their homes rest, even if they own the physical building, we decided to change questions referring to “your property” to “your home.” Upon request of the Colorado State Forest Service – Salida Field Office, the survey also asked residents about the acceptability of thinning vegetation on nearby public lands to reduce wildfire risk. Please refer to Appendix B for the full Mobile Home Park Wildfire Study survey and cover letter.

Recruitment Strategy and Survey Distribution

Given the low survey response rate among mobile home park residents in the Lake County Wildfire Study, we designed the Mobile Home Park Wildfire Survey recruitment and distribution strategy specifically to increase participation among residents. There are many possible methods to reach “hard to reach” populations like the residents in our study (Shaghaghi et al., 201138). Our research balanced efforts to tailor methods to the mobile home context with the desire to maintain consistency and compatibility with the methods and data collection of the Lake County Wildfire Study. To increase the accessibility of the survey, we shortened its length and printed the survey and cover letter in Spanish and English. The survey package also included an addressed and stamped return envelope and $10 cash appreciation gift for completing the survey.

Another consideration for our recruitment strategy was to dispel potential confusion or misperceptions among residents about the survey package itself, as well as the intent of the survey. At the Fire Marshall’s request, the survey package included “SURVEY” printed in large letters on the envelope to address concerns that residents might negatively perceive a survey package with an official government logo. Survey packages included a cover letter that explained the intent of the survey and encouraged participation. The research team also coordinated with the Fire Marshall to hand-deliver surveys and answer questions from recipients, which he did with a small team of fire department volunteers on November 28, 2023. The Fire Marshall had established relationships with mobile home park residents, and while he coordinated a team of volunteers and did not deliver each package personally, we hypothesized that his physical presence might increase the likelihood of trust in the survey intent and thus bolster participation. As they have in the past when visiting the mobile home parks, the Fire Marshall and volunteers also chose not to wear official fire department uniforms to avoid arousing concern about a group of government officials visiting the mobile home parks.

Participant Consent and Other Ethical Considerations

We had previously secured approval from University of Colorado Boulder Institutional Review Board (IRB) for the Lake County Wildfire Project, called “Researcher-practitioner collaborations for rural community wildfire risk reduction” (Protocol 22-0132) on August 2, 2022. For this project, we submitted an amendment to our protocol with a description of the need to survey mobile home residents, an explanation of our research methods and participant recruitment procedures, and copies of the modified survey and recruitment materials. The amendment was approved by the IRB on October 18, 2023.

Each survey packet included a cover letter, printed in English and Spanish and signed by members of the research team and the Lake County Fire Marshall, which explained the purpose of the study, the people conducting it, research consent documentation, and who to contact with questions or other queries. The cover letter, which is reproduced in Appendix B, explained in plain language that the survey was anonymous, no personally identifiable information such as the respondent’s name or address would be collected, and other standard participant consent information.

The research team discussed extensively how to maximize benefits and reduce potential harms to survey participants (i.e., the principle of beneficence from the Belmont Report; 197939). To increase the chances that the survey might benefit residents, we chose survey measures that could directly inform Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue’s outreach and programs in the mobile home parks. To reduce time burden, the Mobile Home Park Wildfire Survey was only three pages, far shorter than the 16-page survey used in the Lake County Wildfire Study. Furthermore, we designed the survey measures and distribution methods specifically to reduce potential concern from residents about the nature of the survey and to protect respondents’ identities.

Survey Sample

The Mobile Home Park Wildfire Survey, sent just to all residential properties in the three mobile home parks, received 34 responses, for a 13% response rate. Of those responses, slightly more than half used the English version of the survey. Refer to Table 1 for mobile home park-specific response rates. Surveys were distributed to all residences in Mountain View Village East (n=62), Mountain View Village West (n=134), and Mountain Valley Estates (n=65) near Leadville, Lake County, Colorado. To ensure respondent anonymity, respondent addresses were not collected. However, return envelopes were marked with the letter “A,” “B,” or “C,” to distinguish the three mobile home parks in survey responses.

Data Analysis Procedures

The research team compiled and analyzed Mobile Home Park Wildfire Survey data using descriptive statistics, which we present in graphical format in the results below. Full results can also be found in Appendix C. As the Lake County Wildfire Study’s survey data is not yet available, we were not able to compare results between mobile home and non-mobile home residents.

Results and Discussion

This study aimed to gather information about wildfire risk characteristics, evacuation preparedness, and outreach preferences of three mobile home park communities in Lake County, Colorado. We first present secondary data collected by local wildfire professionals, assessing wildfire risk based on 13 attributes in four categories. We compare rapid wildfire risk assessments for all parcels in the mobile home park communities (n=259) to parcels in other selected communities (n=518) in Leadville, Colorado. Then we describe household survey responses from residents of the three mobile home parks (n=34, 13% response rate). When interpreting household survey results, it is important to note the small number of respondents.

Risk Assessments: How Is Parcel-Level Wildfire Risk Similar or Different Between Mobile Home and Non-Mobile Home Housing?

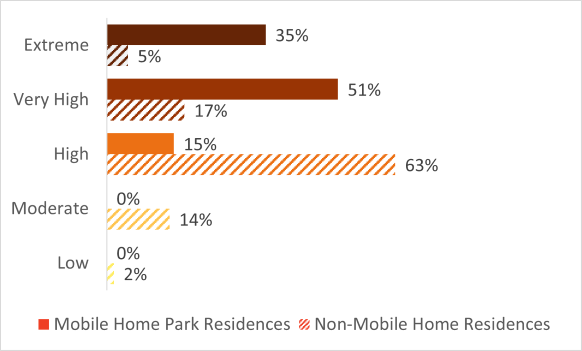

The overall risk rating for each parcel in the study area represents a sum of scores from 13 wildfire risk attributes. As all homes in the study area exist in a wildfire-prone landscape, they all hold wildfire risk; the overall risk rating is intended as a coarse measure of relative wildfire risk across a community. While all parcels in the study area tended toward higher risk rating categories, mobile home park parcels’ overall risk ratings were higher on average compared to non-mobile home park parcels. As Figure 2 shows, 86% of the mobile home park parcels had very high or extreme wildfire risk, compared to only 22% of non-mobile home park parcels. Furthermore, none of the mobile home park parcels had moderate or low risk. In contrast, 63% of non-mobile home park parcels were rated as having high risk and 16% were rated as having moderate or low risk.

Figure 2. Overall Wildfire Risk Rating on Mobile Home Parcels and Non-Mobile Home Parcels

Note. Comparison of 259 mobile home parcels and 518 non-mobile home parcels in Lake County. Solid shading indicates mobile home parcels. Diagonal shadding indicates non-mobile home parcels.

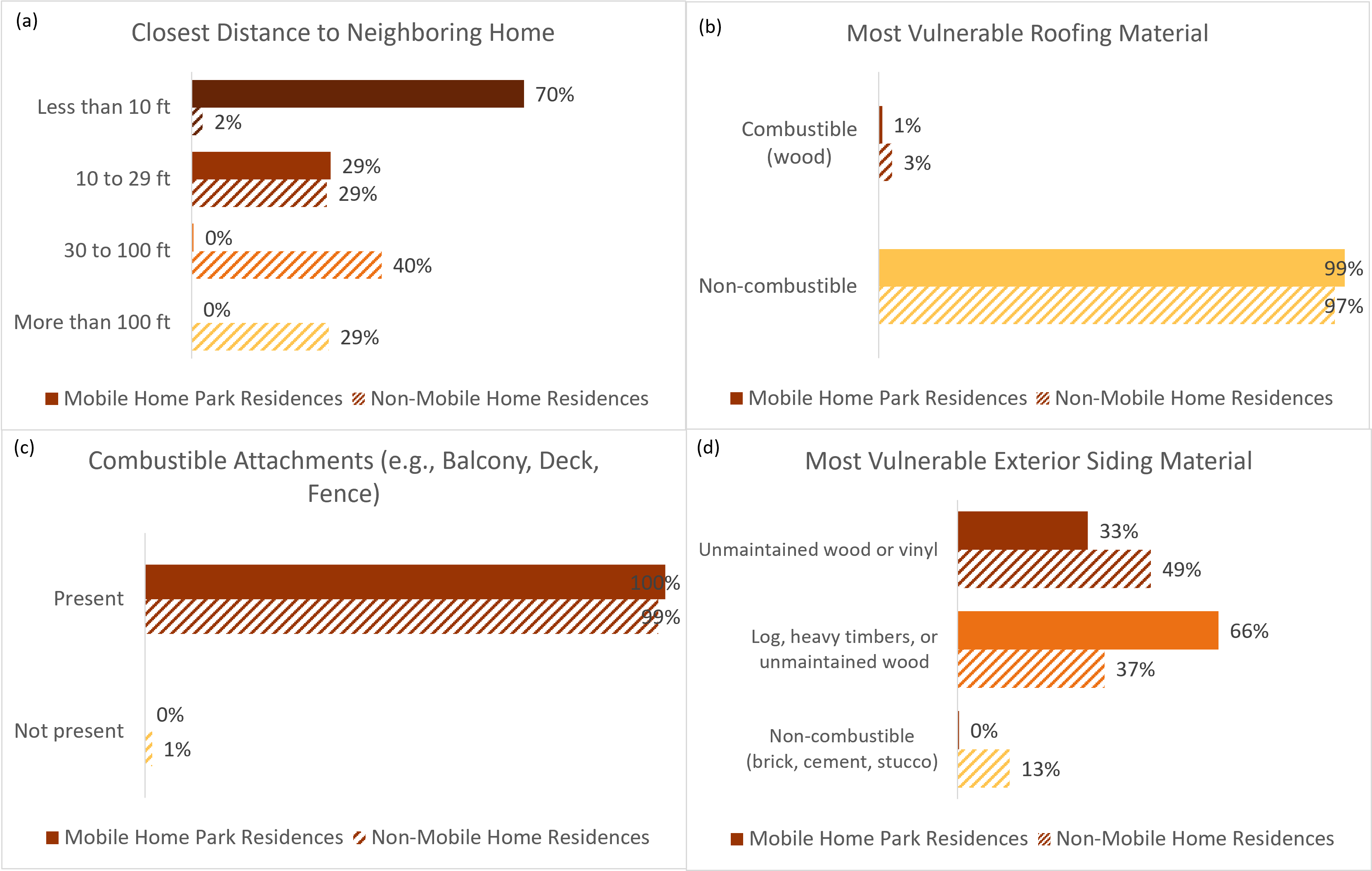

The ignitability of a structure is shaped by the materials used in its construction and its proximity to other buildings. Figure 3 compares four home ignition risk attributes on mobile home park and non-mobile home park parcels. As seen in figure 3a, mobile home park homes were notably closer to neighboring homes than non-mobile home park homes; all mobile home park homes were less than 30 feet from a neighboring home, and 70% were less than 10 feet. In comparison, 69% of non-mobile home park homes were at least 30 feet from a neighboring home. The proximity of mobile home park homes to each other provides critical context for understanding the wildfire risk mitigation problem in this housing type. Contrary to their name, most mobile homes are not easily moved, and as such, home proximity is a substantial risk factor that residents generally cannot address.

Figure 3. Home Ignition Risk Attributes on Mobile Home and Non-Mobile Home Parcels

Note. Comparison of 259 mobile home parcels and 518 non-mobile home parcels in Lake County. Solid shading indicates mobile home parcels. Diagonal shadding indicates non-mobile home parcels.

Other risk attributes associated with home ignition include the roofing materials, siding, and the presence of combustible attachments. As seen in figure 3b, mobile home park and non-mobile home park homes were similar in that almost all had non-combustible roofing materials, which lowered their wildfire risk, and as seen in figure 3c, almost all had combustible attachments, like balconies, decks, and fences, which increased their wildfire risk. However, as seen in figure 3d, mobile home park homes had slightly less combustible siding materials than non-mobile home park homes. Overall, mobile and non-mobile home park homes are similar in terms of these risk attributes. However, it is important to note that these risk attributes may be more difficult for mobile home park residents to address, especially if they are renters or have limited financial resources for home improvements.

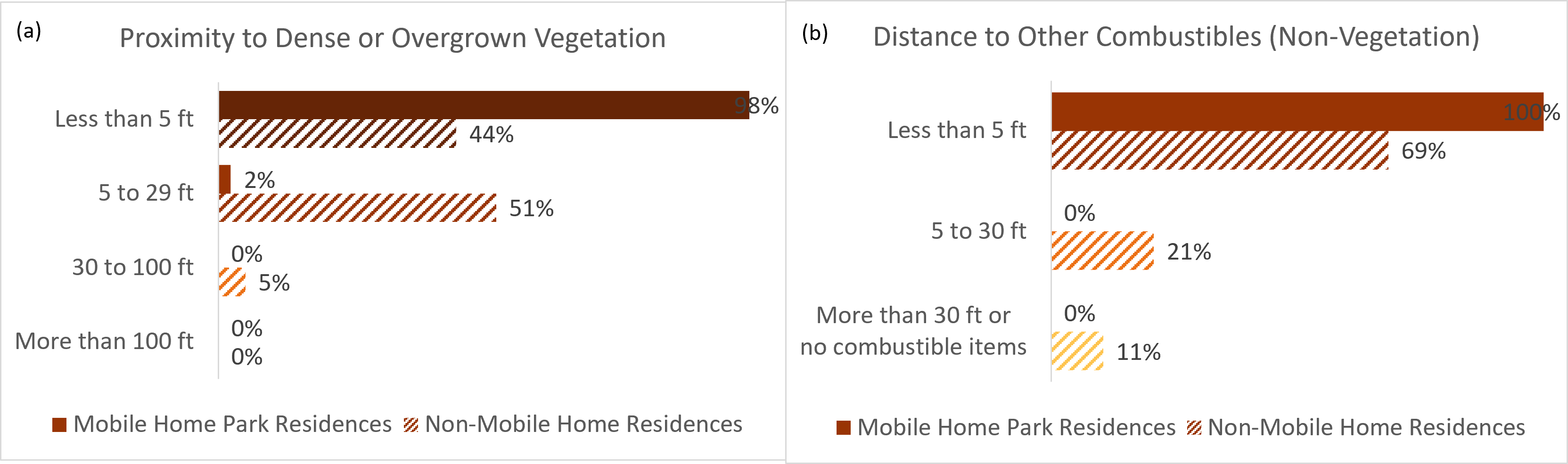

Close proximity or direct contact with vegetation and other combustible materials also affects home ignition risk, as these items can ignite and transfer flames to the home itself. The distance from a home to such combustible materials is part of the home’s ‘defensible space,’ intended to allow space within which first responders can defend the structure from fire. As seen in figure 4, most study area homes had limited defensible space (less than 30 feet), but mobile home park homes fell to the extreme end of the spectrum. Figure 4a shows that 98% of mobile home park parcels fell into the riskiest “less than 5 feet” category for distance to dense, overgrown, or unmaintained vegetation (e.g., dense shrubbery, a tree whose branches touch the roof). A wildfire professional who conducted these assessments noted that given the mobile homes’ proximity, trees were necessarily growing close to homes, and any given tree affected multiple homes’ defensible space. For example, a single ponderosa pine had branches touching or overhanging the roofs of more than 5 structures. Figure 4b shows that 100% of mobile home park homes were less than 5 feet from other combustibles (e.g., propane tanks, woodpiles, deck furniture), the riskiest category. The proximity of mobile homes may also affect distance to other combustibles, as residents do not have enough space around their home to place such items at an adequate distance. While these results indicate that defensible space is a concern for all residents, mobile home park residents might benefit from tailored outreach about defensible space. Mobile home park residents may not have as much flexibility in terms of where to plant vegetation, or may not be able to alter vegetation, since they do not own the land on which their home rests. As such, encouraging residents to move or dispose of non-vegetation combustibles may be the better option for outreach.

Figure 4. Defensible Space Risk Attributes on Mobile Home and Non-Mobile Home Parcels

Note. Comparison of 259 mobile home parcels and 518 non-mobile home parcels in Lake County. Solid shading indicates mobile home parcels. Diagonal shadding indicates non-mobile home parcels.

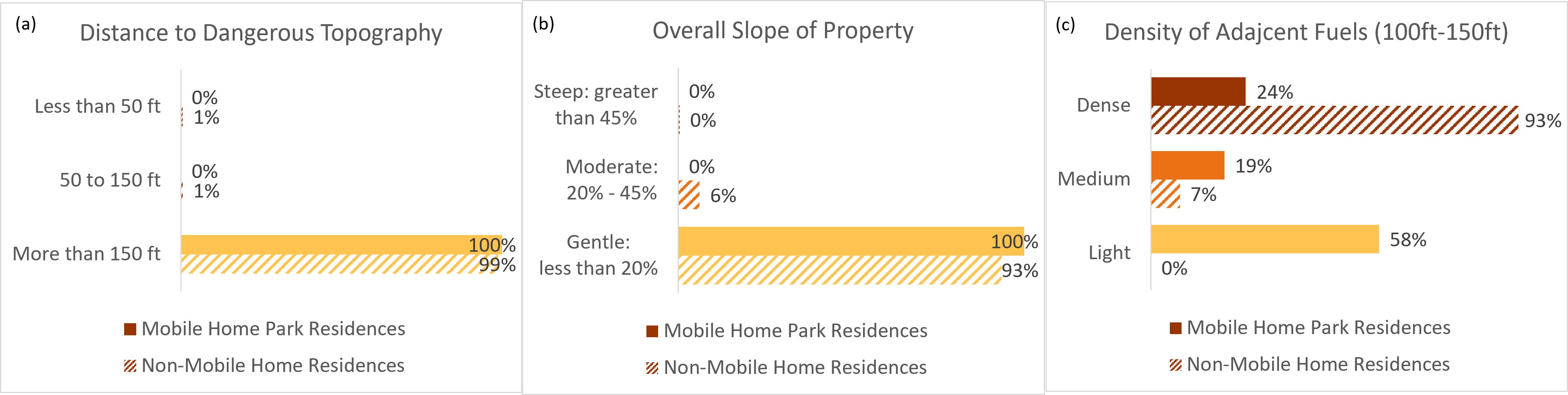

Wildfire risk posed by background conditions beyond the parcel—which can exacerbate wildfire behavior—were generally low, particularly for the mobile home park parcels. As seen in figures 5a and 5b, almost all parcels were more than 150 feet from dangerous topography (e.g., a ridge, steep canyon, or drainage) and were situated on gently sloping land (less than 20%). Figure 5c depicts the density of vegetation 100-150 feet from the home. Most mobile home park parcels had light adjacent fuels (58%), although some had medium (19%) or dense (24%) adjacent fuels. In contrast, most non-mobile home park parcels had dense vegetation 100-150 feet from the home (93%). The difference in background fuels conditions between these two parcel types is not surprising. The mobile home parks, except for a few small sections, were generally surrounded by grassy areas, whereas the non-mobile home park homes were often intermixed with the forest. While sparse vegetation surrounding the mobile home parks reduces their wildfire risk, it is possible that this attribute may affect residents’ willingness to remove trees near their homes to improve defensible space, as such trees provide privacy, shade, and other benefits.

Figure 5. Background Condition Risk Attributes on Mobile Home and Non-Mobile Home Parcels

Note. Comparison of 259 mobile home parcels and 518 non-mobile home parcels in Lake County. Solid shading indicates mobile home parcels. Diagonal shadding indicates non-mobile home parcels.

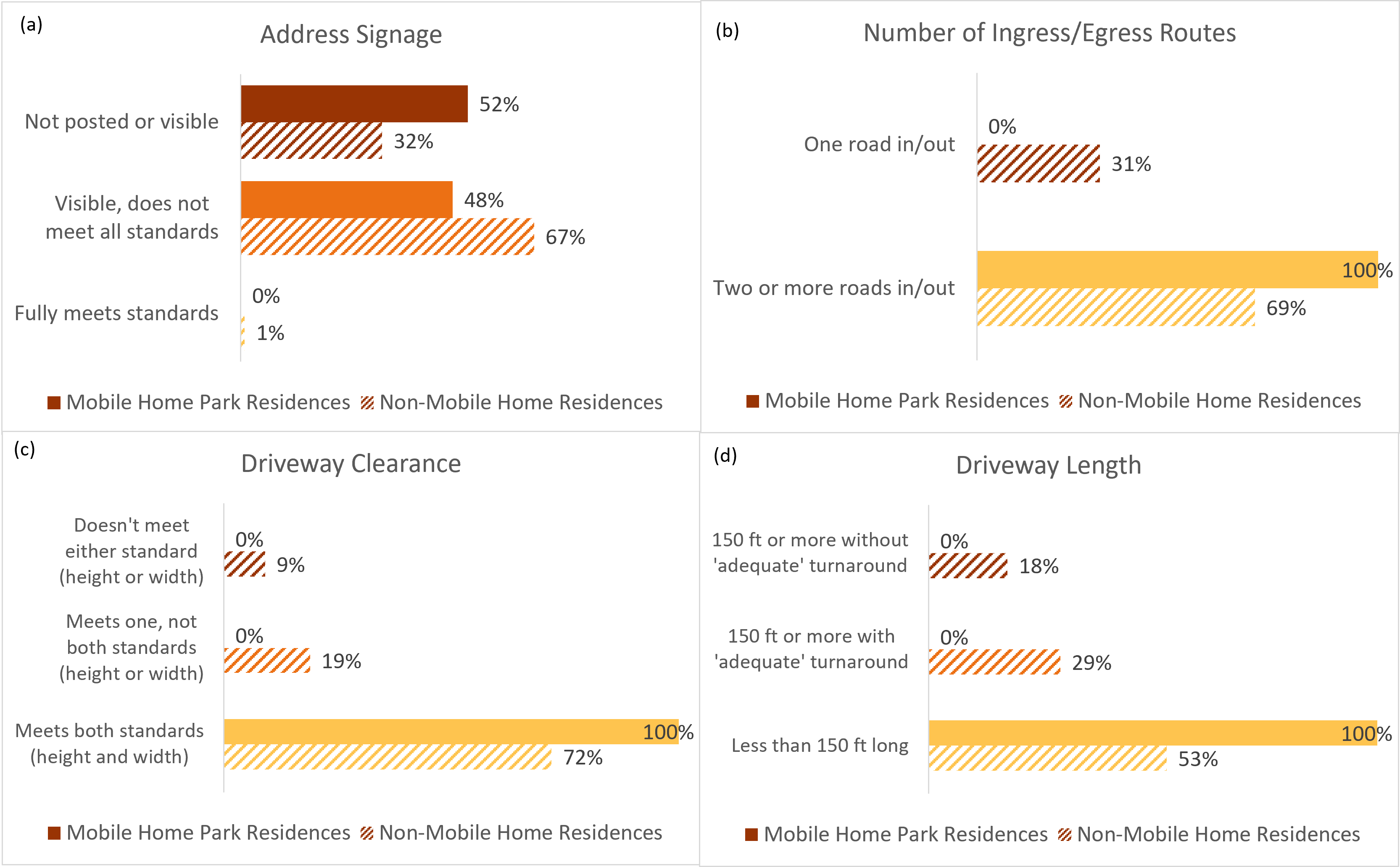

During a wildfire, residents must have evacuation (egress) route options and emergency responders must be able to safely identify and access properties with fire engines. As seen in figure 6a, in both community types, almost none of the parcels had address signage that was visible from the road and fully met safety standards, characteristics that are critical for fire professionals when locating an address in dark, smoky conditions. However, as the mobile home parks were sparsely vegetated and closely situated, it may be easier for fire professionals to identify where to focus their efforts. Furthermore, as seen in figure 6b, all mobile home park parcels had two or more egress routes, and as seen in figures 6c and 6d, adequate driveway clearance and length for a Type 1 fire engine to access the homes and turn around to leave the homes. These results suggest that reducing access-related risk may not be a priority for Leadville/Lake County Fire Rescue when outreaching to the mobile home parks.

Figure 6. Access Risk Attributes on Mobile Home and Non-Mobile Home Parcels

Note. Comparison of 259 mobile home parcels and 518 non-mobile home parcels in Lake County. Solid shading indicates mobile home parcels. Diagonal shadding indicates non-mobile home parcels.

Awareness: How Do Mobile Home Park Residents Perceive Wildfire Risk to Their Homes?

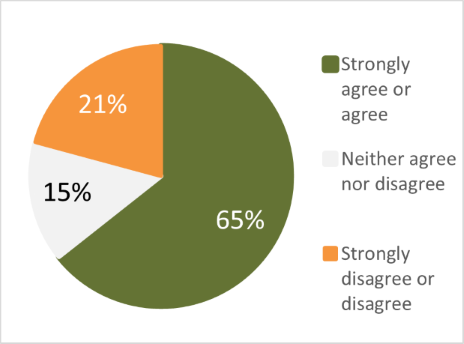

The Mobile Home Park Wildfire Survey asked whether respondents agreed with the statement, “my home is at risk of wildfire.” As seen in figure 7, two-thirds of respondents (66%) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement; however, 15% neither agreed nor disagreed, and 21% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed. Wildfire risk awareness can be an important precursor to mitigation or evacuation preparedness behaviors. As such, outreach to promote wildfire risk awareness may be an important first step for Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue.

Figure 7. Agreement With Statement, “My Home Is at Risk of Wildfire”

Note. There were 34 survey responses to this question.

Evacuation: To What Extent Are Mobile Home Park Residents Prepared to Evacuate in The Event of Wildfire?

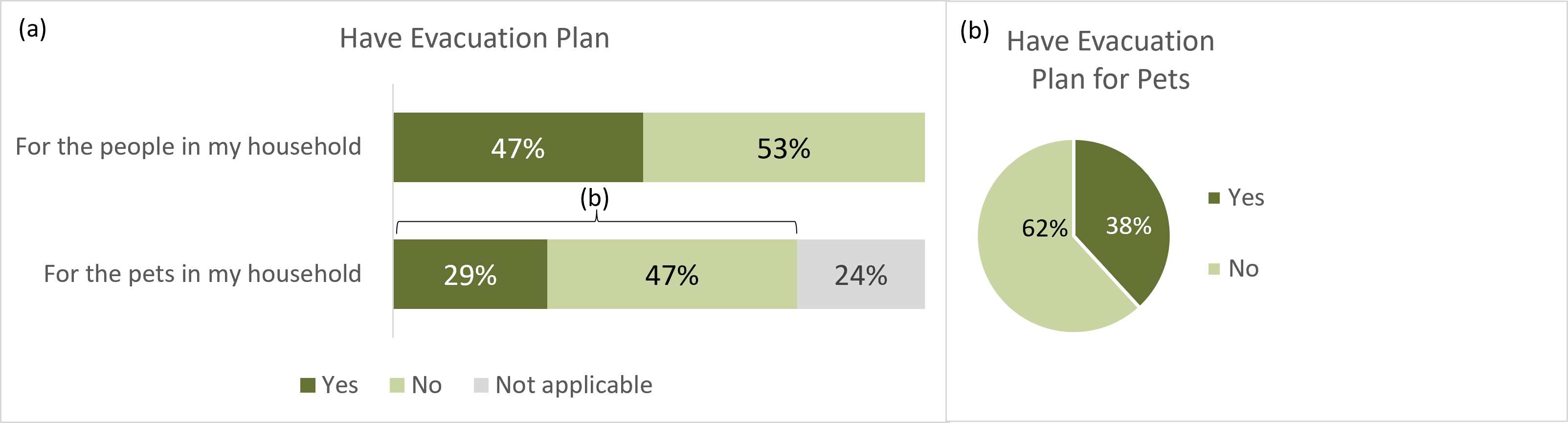

Evacuation preparedness may be an important opportunity for education. As shown in figure 8a, only 47% of respondents reported having an evacuation plan for people in the household, and as shown in figure 8b, only 38% of respondents with pets had an evacuation plan for their pets. Given the density of mobile homes park homes, mobile home park residents may need to evacuate quickly; as such, emergency planning is critical.

Figure 8. Evacuation Planning for People and Pets

Note. Figure 8a represents 34 survey responses; figure 8b represents 26 survey responses.

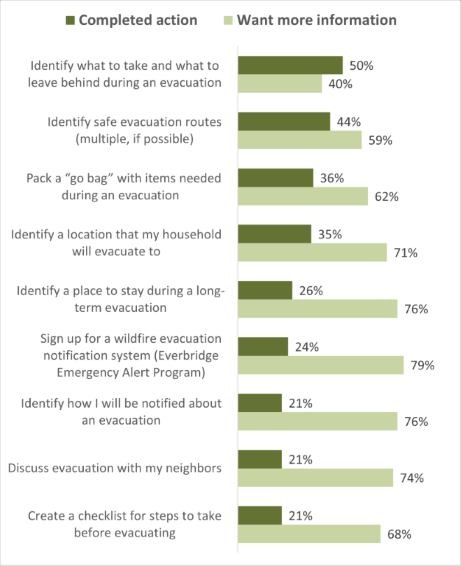

Figure 9 shows that less than half of respondents had completed the evacuation preparedness actions asked about on the survey, including identifying safe evacuation routes (44%), packing a “go bag” (36%), identifying a location for the household to evacuate to (35%), or signing up for a wildfire evacuation notification system (24%). However, respondents were eager for more information about these actions. Over 59% of respondents wanted more information about the preparedness actions listed, except for identifying what to take and what to leave behind (40%). These results confirm that evacuation preparedness may be a fruitful topic for outreach.

Figure 9. Evacuation Preparations Completed and Desire for More Information

Note. Data is ordered by activities completed. The number of respondents varied by question and evacuation activity. For completing the activity, there were 7-17 respondents, depending on the action. For wanting more information, there were 17-27 respondents, depending on the activity.

Communication: How Do Mobile Home Park Residents Prefer to Receive Wildfire Risk Information?

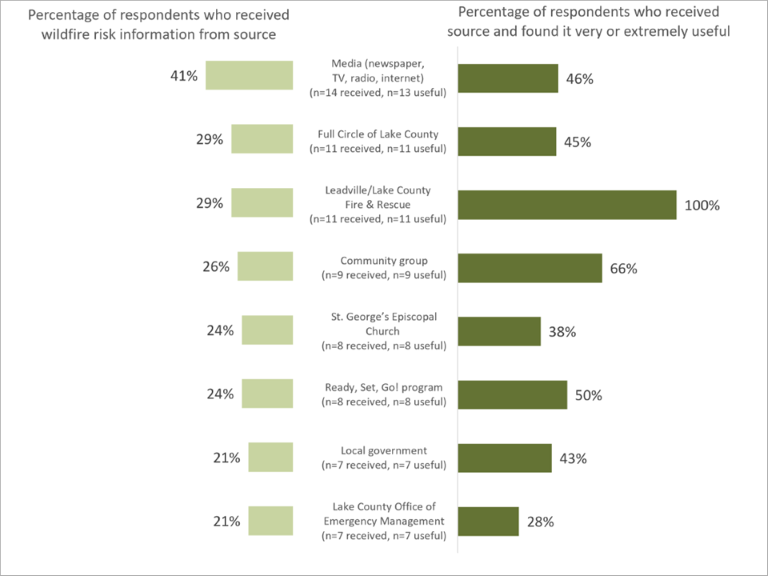

The survey asked respondents from whom they receive information about wildfire risk and whether they found those sources useful. Results were inconclusive on the best way to provide wildfire risk information to mobile home park residents. Of the information sources and channels listed in the survey, none reached a majority of respondents. In fact, as figure 10 shows, less than a third of respondents received information from the sources listed in the survey, except for media (newspaper, TV, radio, internet), which 41% of respondents reported. Furthermore, fifteen respondents reported that they received none of the sources. It is possible that mobile home park residents turn to other sources for wildfire risk information. Alternatively, given the many ways in which individuals currently consume information, it is possible that no single source of information could reach all residents in a particular community. Regardless, these results suggest the need for further efforts to provide wildfire risk information in these communities.

The survey also asked respondents to report the usefulness of each source—measured in the survey on a scale from “not at all useful” to “extremely useful.” As shown in figure 10, all respondents who received information from Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue found it very or extremely useful, indicating that mobile home park residents may be open to further outreach efforts from the fire department. Furthermore, two thirds (66%) of respondents rated the non-specific option of “community group” as very or extremely useful (66%). If Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue can identify these groups, they may be able to engage with residents through these trusted organizations. However, less than half of respondents rated as very or extremely useful the two sources that we added to the survey for their perceived connections with mobile home park residents (St George’s Episcopal Church and Full Circle of Lake County; 38% and 45%, respectively), suggesting that while these organizations may be important sources of information overall, they are not currently providing wildfire risk information. Overall, Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue may benefit from further investigation into how mobile home park residents receive public safety information; however, results also highlight that the fire department is a trusted source itself.

Figure 10. Wildfire Risk Information Source Preferences

Note. Respondents either selected that they did not receive a source or rated its usefulness. Survey responses varied by source, ranging from 7-13 respondents. The following sources are local community groups within Leadville who may be providing wildfire risk information to residents: St George’s Episcopal Church (community pantry), Ready, Set, Go! Program (national program with local chapters), Full Circle of Lake County (local housing organization).

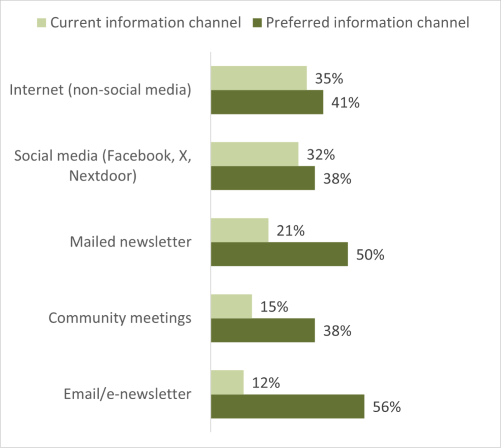

Respondents also reported how they currently receive wildfire risk information, and how they would prefer to. As seen in figure 11, none of the channels listed in the survey were received by more than 35% of respondents. The most preferred information channels were e-newsletter (56%) and mailed newsletter (50%). However, these information channels may require collection of email or mail addresses to be viable. It may be difficult to obtain this information. As described in the research design section, our research team faced significant barriers when attempting to reach mobile home park residents by mail. Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue might consider identifying community groups who could share newsletters and other information with residents via emailing lists or other channels.

Figure 11. Wildfire Risk Information Channel Preferences

Note. Data is ordered by channels currently received. The number of respondents varied by question and channel. For currently receiving channels, there were 4-12 respondents, depending on the channel. For preferred channels, there were 13-19 respondents, depending on the channel.

Barriers and Incentives: What Prevents Mobile Home Park Residents from Mitigating, and What Might Encourage Them?

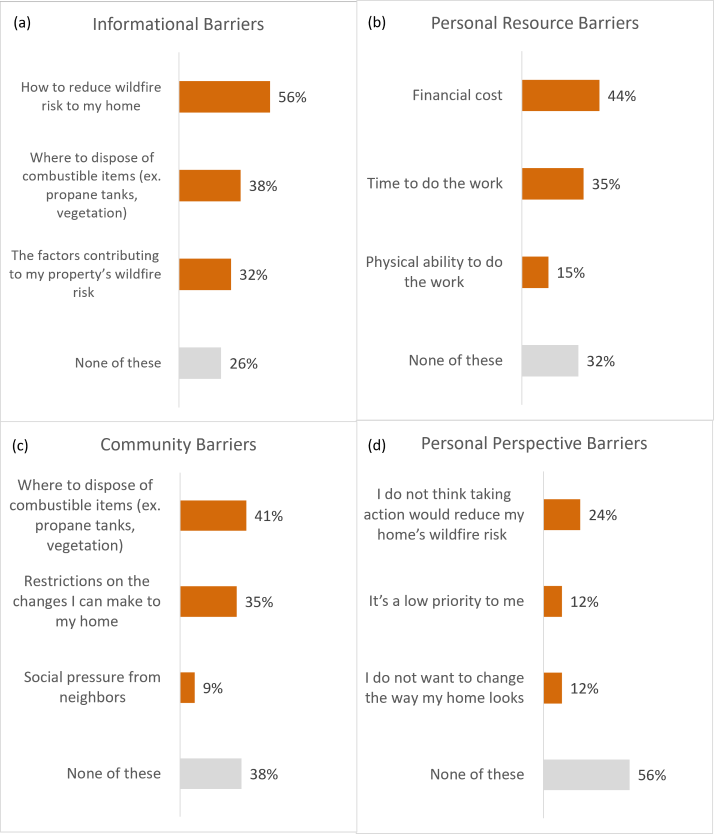

The survey asked respondents about barriers that might prevent them from taking action to reduce wildfire risk to the home. As seen in figure 12a, information about how to reduce wildfire risk to the home (56%) was the most reported barrier. Some respondents also reported other information barriers including knowing where to dispose of combustible items (38%) and knowing factors that contributed to their homes’ risk (32%). As seen in figure 12b, personal resource barriers were also commonly reported, including financial cost (44%), and time to do the work (35%), although only 15% of respondents reported physical ability as a barrier. These results align with socioeconomic indicators for the area, which report low median income and age in this Census tract (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020b). As seen in figure 12c, some respondents also reported community barriers, including limited options for disposing of combustible items (41%) and restrictions to changes residents can make to their homes (35%); notably, only 9% of respondents reported social pressure from neighbors as a barrier to mitigation. As seen in figure 12d, the least common barriers were personal perspectives: Only 24% of residents thought taking action would not reduce their home’s wildfire risk whereas 12% reported wildfire risk mitigation is a low priority for them and 12% reported they did not want to change the way their property looks. Overall, these results indicate that respondents are open to making changes to their properties and have the physical capacity to do it. However, respondents may not know how to reduce risk or where to dispose of combustible items, and they may lack the financial resources necessary to take action.

Figure 12. Barriers to Taking Action to Reduce Wildfire Risk to Home

Note. There were 33 survey respondents to each of the questions represented in the figures above.

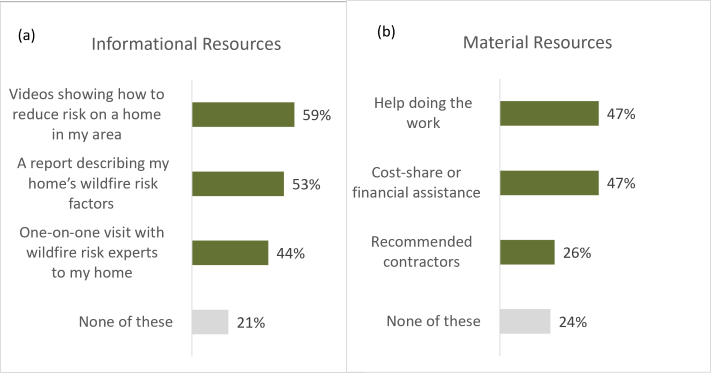

Respondents were also asked about resources that would encourage them to mitigate their wildfire risk. As Figure 13a shows, most respondents said that informational resources, especially those with mitigation information tailored to their home—such as videos showing how to reduce risk to a similar home (59%) or a diagnostic report describing their home’s wildfire risk factors (53%)—would motivate them to take action. Slightly less, but still a significant number, said a one-on-one visit with a wildfire risk expert (44%) would be helpful. As seen in figure 13b, about half of respondents indicated that material resources—such as help doing the work (47%) or a cost-share (47%)—would encourage them to mitigate wildfire risk. The least likely resource to encourage mitigation behaviors among residents was providing a list of recommended contractors (26%). Overall, these results indicate that more informational and financial resources would encourage mitigation. Importantly, such resources might be most effective in encouraging mitigation if they are tailored to the specific context and needs of mobile home park residents (Champ et al., 2022; Meldrum et al., 2024).

Figure 13. Resources That Would Encourage Respondents to Reduce Wildfire Risk to Home

Note. Figure 13a represents 34 survey responses; figure 13b represents 32 survey responses.

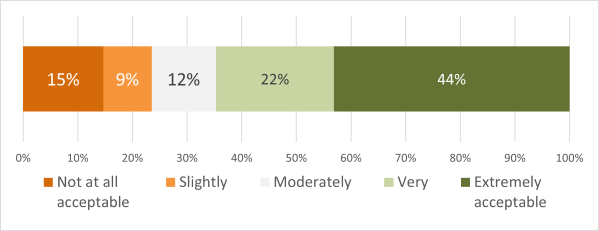

The survey also asked residents about the acceptability of removing trees and other vegetation (“thinning”) on nearby public lands. As figure 14 shows, most respondents found this fuel treatment practice very or extremely acceptable (66%). However, 12% only found it moderately acceptable, and 15% found it only slightly or not at all acceptable.

Figure 14. Acceptability of Removing Trees and Other Vegetation (Thinning) on Nearby Public Lands

Note. Figure 14 represents 34 survey responses.

Conclusions

Among WUI community types, mobile home parks are uniquely vulnerable to wildfire. A key component of wildfire risk to mobile home parks is the proximity of structures, which increases the likelihood of home-to-home wildfire transmission. Home proximity also limits risk mitigation opportunities in mobile home parks. For example, standard defensible space zones (typically 10-30 feet) intended to reduce home ignitions and provide safe zones in which to fight fire are simply impossible to maintain when homes are situated in close proximity. Immutable risk to mobile home parks raises questions about how fire organizations can best engage and support these communities in wildfire readiness activities.

Our results indicate two main ways mobile home park residents can address wildfire risk. First, some of the factors that contribute to wildfire risk to mobile homes are changeable. For example, removal or reduction of combustible materials near the home is an important step to reduce the likelihood of home ignition. These factors present an opportunity for outreach and action. Further, identifying and addressing barriers to action and providing resources to encourage action can contribute to building a pathway to reduce wildfire risk. In Lake County, our results highlight the potential for combined educational outreach and resource programming, such as hosting a free combustible materials disposal day, to encourage wildfire risk reduction.

More critical, however, is the priority of life safety. Fostering residents’ understanding of and engagement in evacuation preparedness increases capacity for residents to take action when it is necessary to flee from harm’s way. Further, quick and safe evacuations increase opportunities for first responders to turn towards the task of fire suppression. In the study area, only a small portion of mobile home park respondents reported receiving wildfire risk information. The gap between information shared and received highlights an important outreach opportunity. Survey respondents indicated a desire for information about wildfire mitigation and evacuation preparedness, suggesting receptivity to engagement. Importantly, since mobile home park residents may benefit from extra time or depth of relationship for ethical and effective engagement, we recommend the phase of disaster risk mitigation and preparedness as the appropriate time for local fire organizations to begin building relationships.

Recommendations for Practitioners or Policymakers

Drawing from the results presented in this report, we present a list of six recommendations for policymakers and practitioners aiming to encourage wildfire risk mitigation and evacuation preparedness in mobile home park communities.

- Develop wildfire risk information sharing campaigns through the partnership of fire and rescue professionals and local community groups.

- Consider communicating about wildfire risk via preferred channels: videos, reports and/or e-newsletter and mailed newsletter.

- Wildfire risk information may be more effective if communicated in both Spanish and English.

- Consider financial barriers when designing programs to encourage risk mitigation.

- When promoting wildfire risk mitigation, focus on characteristics residents can change, such as removing combustible items near the home.

- In wildfire outreach, focus on evacuation preparedness, including evacuation planning, signing up for evacuation notifications, identifying safe evacuation routes and destinations, and packing a “go bag.”

Strengths and Limitations

We designed the Mobile Home Park Wildfire Study to align methodologically with a related study, the Lake County Wildfire Study, which we are currently conducting. Aligning our study area with that of the Lake County Wildfire Study allowed us to leverage parcel-level risk assessment data for the mobile home parks in our study area. Furthermore, using the same survey questions will enable us to contextualize mobile home park residents’ survey responses by comparing them with responses from the broader study area. The comparability of our data may make it more useful for our local partners, as they can design programs and outreach with their whole jurisdiction in mind. However, our desire for comparability with the Lake County Wildfire Study also limited our choices for what to ask on our survey. Furthermore, because residents had already received multiple requests to complete the 16-page Lake County Wildfire Study survey, we chose to send a 3-page survey in a single recruitment effort, hoping to avoid causing research fatigue (Clark, 200840).

Our methodological choices balanced the needs of our partners and our consideration for research participants; however, these choices also affected our survey response rate and the data we collected. The small population of mobile home park residents and the low response rate limits the conclusions that might be drawn from the data, both in Lake County and more broadly. For example, response rates were notably lower in one of the three mobile home parks, and thus results may not reflect the perspectives of those residents. Additionally, the short length of the survey and our desire to ask questions most relevant to our partners’ programs meant we did not collect demographic or homeownership information that would have been helpful for characterizing residents’ capacity for wildfire risk mitigation.

Compared to the Lake County Wildfire Study’s single survey response from the mobile home parks in the study area, our research effort’s modest response rate might be considered a success. Many factors may have contributed to the increase in responses, including translation of the survey to Spanish, hand-delivery by a partner with connections to the residents, inclusion of a $10 appreciation gift, and the shortened length of the survey. However, in hindsight, we could have made further efforts to raise awareness among residents about the survey and increase the response rate. For example, we could have asked a local organization with connections to the mobile home parks to promote the survey by making an announcement or putting up flyers. The fire department personnel who delivered the surveys did not speak Spanish, which also may have limited their ability to explain the survey when hand-delivering; finding Spanish-speaking collaborators may have also improved the response rate and residents’ recruitment experience.

Successful completion of this project depended upon established relationships between the research team and local collaborators. Partners in the local fire department and local division of the state forest service aided in selecting and refining survey questions to be comprehensible to mobile home park residents and relevant to wildfire outreach and program development. Local partners were also essential to overcoming several mobile home resident survey delivery challenges. While these partnerships were critical to the project’s success, practitioners do not operate on research schedules and their availability can affect project timelines. Researchers aiming to conduct research on wildfire preparedness in mobile home parks should consider how to develop local partnerships, and the time needed for productive collaboration. More time and effort invested in building trust and partner relationships, as well as potentially expanding the partners included, can deepen and strengthen such research.

Future Research Directions

Future activities for this project include the full comparison of household survey responses of mobile home park to non-mobile home park respondents. Full study results will be shared with project partners at Colorado State Forest Service—Salida Field Office and Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue. We will continue to work with our partners to foster collaborative engagement and explore opportunities to expand or tailor their community outreach and engagement efforts.

Further, alternative research methods, such as focus groups or interviews may provide important contextual information that a survey cannot gather. As mobile home park communities are systematically understudied, the open-ended nature of focus groups and interviews may help researchers explore topics unknown at research planning stages. Research that also considers potential differences between manufactured home property owners and renters related to wildfire preparedness is needed. With limited existing research in mobile home park study areas, such additional information is critical to build fuller understandings of the unique challenges of living with wildfire in the WUI.

Acknowledgments. This project was made possible through our partnership and collaboration with Colorado State Forest Service—Salida Field Office and Leadville/Lake County Fire-Rescue and through funding from FEMA Quick Response Award, University of Colorado Outreach Awards Program, and sustained funding from the USDA Fire and Aviation Management.

References

-

Balshi, M. S., McGuirez, A. D., Duffy, P., Flannigan, M., Walsh, J., & Melillo, J. (2009). Assessing the response of area burned to changing climate in western boreal North America using a Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS) approach. Global Change Biology, 15(3), 578–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01679.x ↩

-

Litschert, S. E., Brown, T. C., & Theobald, D. M. (2012). Historic and future extent of wildfires in the Southern Rockies Ecoregion, USA. Forest Ecology and Management, 269, 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2011.12.024 ↩

-

Westerling, A. L., Hidalgo, H. G., Cayan, D. R., & Swetnam, T. W. (2006). Warming and Earlier Spring Increase Western U.S. Forest Wildfire Activity. Science, 313(5789), 940–943. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1128834 ↩

-

Theobald, D. M., & Romme, W. H. (2007). Expansion of the U.S. wildland–urban interface. Landscape and Urban Planning, 83(4), 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.06.002 ↩

-

Gill, A. M., & Stephens, S. L. (2009). Scientific and social challenges for the management of fire-prone wildland–urban interfaces. Environmental Research Letters, 4(3), 034014. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/4/3/034014 ↩

-

Schoennagel, T., Balch, J. K., Brenkert-Smith, H., Dennison, P. E., Harvey, B. J., Krawchuk, M. A., Mietkiewicz, N., Morgan, P., Moritz, M. A., & Rasker, R. (2017). Adapt to more wildfire in western North American forests as climate changes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(18), 4582–4590. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1617464114 ↩

-

Durst, N. J., & Sullivan, E. (2019). The Contribution of Manufactured Housing to Affordable Housing in the United States: Assessing Variation Among Manufactured Housing Tenures and Community Types. Housing Policy Debate, 29(6), 880–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1605534 ↩

-

Economic & Planning Systems, Inc. (2018). Lake County Housing Needs Assessment. EPS #173017, Economic & Planning Systems, Inc., Denver, CO, 49. ↩

-

Environmental Protection Agency (n.d.). Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (Version 2.2). Retrieved January 22, 2024, from https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/ ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020a). Leadville North CCD, Lake County, Colorado - Decennial Census. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://data.census.gov/table?g=060XX00US0806592242 ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020b). Leadville North CCD, Lake County, Colorado – American Community Survey. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://data.census.gov/table?g=060XX00US0806592242 ↩

-

Collins, T. W., & Bolin, B. (2009). Situating Hazard Vulnerability: People’s Negotiations with Wildfire Environments in the U.S. Southwest. Environmental Management, 44(3), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-009-9333-5 ↩

-

Pierce, G., Gabbe, C. J., & Rosser, A. (2022). Households Living in Manufactured Housing Face Outsized Exposure to Heat and Wildfire Hazards: Evidence from California. Natural Hazards Review, 23(3), 04022009. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000540 ↩

-

Meldrum, J. R., Barth, C. M., Goolsby, J. B., Olson, S. K., Gosey, A. C., White, J. (Brad), Brenkert-Smith, H., Champ, P. A., & Gomez, J. (2022). Parcel-Level Risk Affects Wildfire Outcomes: Insights from Pre-Fire Rapid Assessment Data for Homes Destroyed in 2020 East Troublesome Fire. Fire, 5(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5010024 ↩

-

Meldrum, J. R., Brenkert-Smith, H., Champ, P. A., Falk, L., Wilson, P., & Barth, C. M. (2018). Wildland–urban interface residents’ relationships with wildfire: Variation within and across communities. Society & Natural Resources, 31(10), 1132–1148. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2018.1456592 ↩

-

Caton, S. E., Hakes, R. S. P., Gorham, D. J., Zhou, A., & Gollner, M. J. (2017). Review of Pathways for Building Fire Spread in the Wildland Urban Interface Part I: Exposure Conditions. Fire Technology, 53(2), 429–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-016-0589-z ↩

-

Hakes, R. S. P., Caton, S. E., Gorham, D. J., & Gollner, M. J. (2017). A Review of Pathways for Building Fire Spread in the Wildland Urban Interface Part II: Response of Components and Systems and Mitigation Strategies in the United States. Fire Technology, 53(2), 475–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-016-0601-7 ↩

-

Quarles, S. L., Valachovic, Y., Nakamura, G. M., Nader, G. A., & De Lasaux, M. J. (2010). Home survival in wildfire-prone areas: Building materials and design considerations. ANR Publication 8393, University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources, Richmond, CA, 22. https://doi.org/10.3733/ucanr.8393 ↩

-

Grajdura, S., Qian, X., & Niemeier, D. (2021). Awareness, departure, and preparation time in no-notice wildfire evacuations. Safety Science, 139Litschert, 105258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105258 ↩

-

Paveglio, T. B., Moseley, C., Carroll, M. S., Williams, D. R., Davis, E. J., & Fischer, A. P. (2015). Categorizing the Social Context of the Wildland Urban Interface: Adaptive Capacity for Wildfire and Community “Archetypes.” Forest Science, 61(2), 298–310. https://doi.org/10.5849/forsci.14-036 ↩

-

Warziniack, T., Champ, P., Meldrum, J., Brenkert-Smith, H., Barth, C. M., & Falk, L. C. (2019). Responding to risky neighbors: testing for spatial spillover effects for defensible space in a fire-prone WUI community. Environmental and Resource Economics, 73, 1023-1047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-018-0286-0 ↩

-

Sullivan, E. (2018). Manufactured Insecurity: Mobile Home Parks and Americans’ Tenuous Right to Place. Univ of California Press. ↩

-

McConnell, K., & Braneon, C.V. (2024). Post-wildfire neighborhood change: Evidence from the 2018 Camp Fire. Landscape and Urban Planning, 247, 104997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104997 ↩

-

Meldrum, J. R., Champ, P. A., Brenkert-Smith, H., Barth, C. M., McConnell, A. E., Wagner, C., & Donovan, C. (2024). Rethinking cost-share programs in consideration of economic equity: A case study of wildfire risk mitigation assistance for private landowners. Ecological Economics, 216, 108041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.108041 ↩

-

Smith, K., Preston, T., Hernandez, P., Samantha, E., & Powell, B. (2022). Mobile home residents face higher flood risk. Headwaters Economics. https://headwaterseconomics.org/natural-hazards/mobile-home-flood-risk/ ↩

-

McCaffrey, S.M. (2004). Fighting fire with education: What is the best way to reach out to homeowners? Journal of Forestry, 102(5), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/jof/102.5.12 ↩

-

Brenkert‐Smith, H., Dickinson, K. L., Champ, P. A., & Flores, N. (2013). Social amplification of wildfire risk: the role of social interactions and information sources. Risk analysis, 33(5), 800-817. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01917.x ↩

-

Wildfire Research Center (n.d.-a). The WiRē Approach. Wildfire Research Center. https://wildfireresearchcenter.org/approach/ ↩

-

Bamzai-Dodson, A., Cravens, A. E., Wade, A. A., & McPherson, R. A. (2021). Engaging with stakeholders to produce actionable science: a framework and guidance. Weather, Climate, and Society, 13(4), 1027-1041. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-21-0046.1 ↩

-

Champ, P. A., Brenkert-Smith, H., Riley, J. P., Meldrum, J. R., Barth, C. M., Donovan, C., & Wagner, C. J. (2022). Actionable social science can guide community level wildfire solutions. An illustration from North Central Washington, U.S. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 82, 103388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103388 ↩

-

Brenkert-Smith, H., Dalton, D., Puffett, J., Champ, P. A., Barth, C. M., Meldrum, J., Donovan, C., R., Wagner, C., Goolsby, J.B., & Forrester, C. (2023). Living with wildfire in Genesee Fire Protection District, Jefferson County, Colorado: 2022 data report. Res. Note RMRS-RN-99, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO, 123. https://doi.org/10.2737/RMRS-RN-99 ↩

-

Goolsby, J.B., Champ, P. A., Brenkert-Smith, H., Clauson, B.J., Sgroi, R.M., Williams, L., Barth, C. M., Meldrum, J. R., Donovan, C., & Wagner, C. (2023). Living with wildfire in Teton County, Colorado: 2021 data report. Res. Note RMRS-RN-93, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO, 92. https://wildfireresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/rmrs_rn093.pdf ↩

-

Wildfire Research Center (n.d.-b). Document Library: Community Reports. Wildfire Research Center. https://wildfireresearchcenter.org/document-library/?dfg_active_filter=55 ↩

-

Brenkert-Smith, H., Champ, P. A., Riley, J., Barth, C. M., Donovan, C., Meldrum, J. R., & Wagner, C. (2020). Living with wildfire in the Squilchuck Drainage, Chelan County, Washington: 2020 data report. Res. Note RMRS-RN-87, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO, 125. https://www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs_series/rmrs/rn/rmrs_rn087.pdf ↩

-

Cohen, J. (2019). A More Effective Approach for Preventing Wildland-Urban Fire Disasters. https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2019I1/Downloads/CommitteeMeetingDocument/209011 ↩

-

National Fire Protection Association. (2013). Standard for reducing structure ignition Hazards from Wildland Fire. NFPA, 1144, 30. https://www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/nfpa-1144-standard-development/1144 ↩

-

Wildfire Research Center (2023). WiRē Rapid Assessment Scoring Guide. Wildfire Research Center. https://wildfireresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/RA_training_materials.pdf ↩

-

Shaghaghi, A., Bhopal, R. S., & Sheikh, A. (2011). Approaches to recruiting "hard-to-reach" populations into research: A review of the literature. Health promotion perspectives, 1(2), 86. https://doi.org/10.5681%2Fhpp.2011.009 ↩

-

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. (1979). The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. United States. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html ↩

-

Clark, T. (2008). “We're Over-Researched Here!” Exploring Accounts of Research Fatigue within Qualitative Research Engagements. Sociology, 42(5), 953-970. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038508094573 ↩

Goolsby, J.B., Brenkert-Smith, H., Donovan, C., Boyle, S., Wagner, C., Champ, P., Kuehn, J., & Wittenbrink, S. (2024). Preparing Mobile Home Park Residents for Wildfire in Lake County, Colorado (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 366). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/preparing-mobile-home-park-residents-for-wildfire-in-lake-county-colorado