The SURGE Experience

A Service-Learning Approach to Assessing Disaster Recovery in the U.S. Virgin Islands

Publication Date: 2019

Abstract

Qualified racial and ethnic minorities, as well as those from low-income communities, are underrepresented in hazards mitigation and disaster research in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) disciplines. The SURGE initiative—Minority Scholars from Under-Represented Groups in Engineering and the Social Sciences—began as a National Science Foundation INCLUDES Design and Development Launch Pilot. The program was formed to address this disproportionate underrepresentation and engage these groups in research that addresses the inordinate impacts of disasters on underserved racial and ethnic minority communities, as well as to advance a body of knowledge that represents diversity and creative problem-solving in scholarship and practice.

In June 2018, the SURGE research team conducted a reconnaissance mission in the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) to explore the 2017 impacts of Hurricanes Irma and Maria. SURGE scholars used participatory observation, community listening sessions, and photo documentation as methods to gather data on the long-term recovery process that was being initiated there. Scholars learned from community leaders and on-site partners about the ongoing recovery efforts, participated in a community service activity, and surveyed the visible impacts. This paper offers an account of the SURGE team experience during the reconnaissance mission and highlights the impacts the 2017 hurricane season had on the built and natural environment, as well as its consequences for people in the USVI.

We hypothesized that Hurricanes Maria and Irma had significant negative impacts on both human-built systems (e.g., communication, debris management, hydrological systems, and the integrity of structures and governance) and human-natural environments (e.g., mangrove forests, water quality, vegetation structure, and food security). Furthermore, the human-built environment will have greater negative effects on the human-natural system, which will result in a delay of recovery efforts in the three main islands of St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John. The findings provide strong evidence that the human-built and human-natural systems were not adequately managed, maintained, or developed over time, which made them vulnerable to disasters such as hurricanes.

Introduction

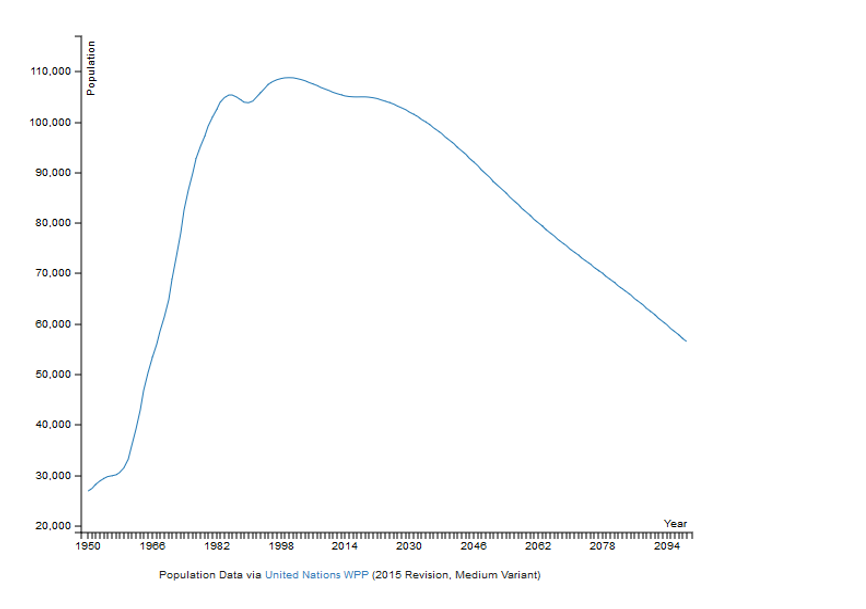

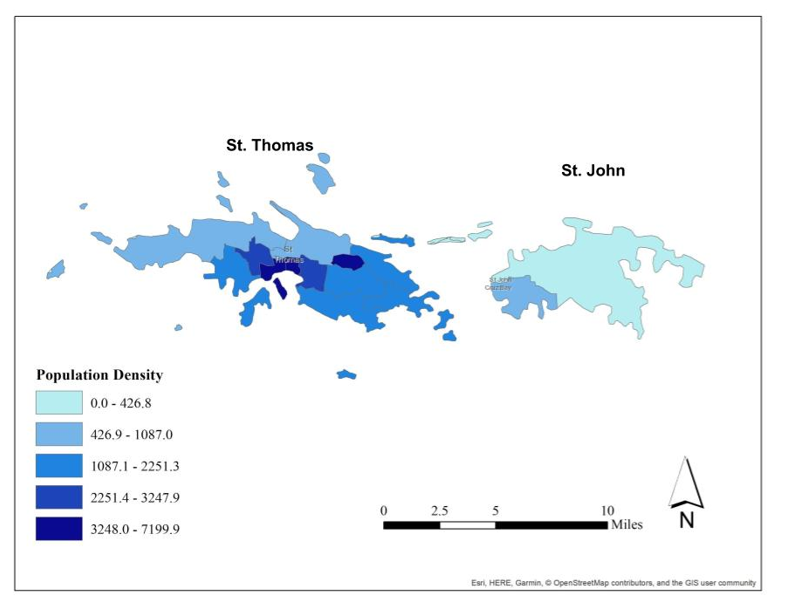

The U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) are an unincorporated, organized territory of the United States in the Caribbean Sea. The USVI has a population of 106,977 people across its three main islands of St. John, St. Croix, and St. Thomas. Although the USVI is one unified territory, several different waves of colonialism (English, French, Spanish, Danish, Dutch, and American) significantly influenced the cultural evolution across these islands, giving each its own distinct character (Virgin Islands Housing Finance Authority, 20151). The population of the USVI has fluctuated over time, with sharp increases between the 1960s and late 1990s, and is projected to decline over time. Most of the population decline is attributed to outward migration caused by the lack of sufficient economic opportunity on the islands as well as a “brain drain” of younger people leaving the islands to pursue educational and economic opportunities on the U.S. continent (Moorhead, 20182; Potter, 20173). St. Thomas is the densest of the islands and home to the capital, Charlotte Amalie, which is the primary center for tourism, government, finance, trade, and commerce. Just west of St. Thomas is St. John, most of which is preserved as the Virgin Islands National Park. Roughly 40 miles due south is St. Croix, known for its more industrial and agrarian character. Figure 1 demonstrates the USVI population change over time, and Figure 2 displays the population density across St. Thomas and St. John.

Figure. 1. U.S. Virgin Islands population change over time.

Figure. 2. St. Thomas and St. John population density.

Similar to other Caribbean countries, tourism is a large sector of the economy for the USVI. Although manufacturing and agriculture can be found within the USVI, the activity is not enough to sustain local needs without the heavy importation of goods. In recent years, the closure of the Hovensa oil refinery on St. Croix in 2012 caused a significant economic impact, and jobs and major tax revenue for the territory had been lost with no clear path for recovery (Kossler, 20174).

The Impact of Hurricanes Irma and Maria on the U.S. Virgin Islands

In the past 147 years, the West Indies Laboratory on St. Croix and other databases have documented more than 18 named seasonal storms/hurricanes and near misses in the USVI. Hurricanes such as Frederic (1979), David (1979), Allen (1981), Gilbert (1989), Hugo (1989), Marilyn (1995), Georges (1998), and most recently Irma (2017) and Maria (2017) have decimated the islands (Sattler et al., 20025; Hubbard, 19926).

Hurricane Irma struck the USVI on September 6, 2017 as a Category 5 hurricane with sustained winds of 106 miles per hour (National Hurricane Center (NHC), 20177). Within two weeks, a second Category 5—Hurricane Maria—further devastated the islands with a wind intensity of 173 miles per hour (NHC, 2017). The hurricanes came with strong winds, storm surges, salt spray, sediment-build up, and heavy rains that resulted in widespread flooding, landslides, and debris buildups (NHC, 2017). As a result of these extreme events, the islands lost important ecosystems (mangrove forests, habitats) and buildings/infrastructure (schools, hospitals, roads), and more than 100,000 residents lost power, all caused by the cascading impacts from the built environment (National Oceanic and Atomospheric Administration National Centers for Environmental Information, 20198). The sustainability and resilience of the human-built and human-natural environments have not been extensively explored before or after hurricanes due to many socioeconomic, political, and communication barriers.

Long-Term Recovery

Current literature shows that there is no such thing as a natural disaster (Smith, 20069; Squires & Hartman, 201310). Disasters happen when a natural event (i.e., hurricane, earthquake) occurs in an area where the human and built environments have existing vulnerabilities that are exacerbated as a result of that event. This poses significant challenges to local officials who are often times overworked, understaffed, and lacking key resources. For small island states, these events constitute a drag on, and act as a significant setback to, development (Kelman & West, 200911). The USVI is currently in the disaster recovery phase, which involves the opportunity to change, recreate, and maintain various societal processes aimed at building resilience to minimize the potential impacts of a future natural event (Atsumi et al., 201812).

In the USVI, long-term recovery efforts are being led by the St. Thomas Recovery Team (STRT)13. This team is made up of diverse community stakeholders who work on coordinating St. Thomas’s long-term recovery, response, and resilience planning in response to Hurricanes Irma and Maria. The group is led by four guiding principles:

Coordination

Collaboration

Cooperation

Communication

STRT has positioned itself as the umbrella organization for agencies and individuals who are working toward the recovery efforts.

A Transdisciplinary Approach to Rapid Reconnaissance

The authors of this report are affiliated with Minority Scholars from Underrepresented Groups in Engineering and the Social Sciences (SURGE) Capacity in Disasters. SURGE focuses on two challenges: (1) the underrepresentation of STEM racial and ethnic minorities in hazards and disasters research and (2) the disproportionate impacts of disasters on underserved racial and ethnic minority communities.

According to Hadorn et al. (2008)14, the transdisciplinary approach is characterized by collaborative and integrated work between scientists of different disciplines and other actors for the formulation of a problem and the design and execution of research. In transdisciplinary research, researchers and local actors affected by a problem share and reflect on the interdependence of scientific and local knowledge to address the complexity of the problem to be solved. This approach becomes a "search for unity of knowledge in addressing issues in the life-world" to obtain a common understanding of it (Hadorn et al., 2008, p. 29). Transdisciplinary research and practice is a relatively new approach which goes “beyond disciplines by weaving a new kind of knowledge” to better address complex societal challenges (McGregor, 200415).

Distinct from an interdisciplinary approach, which draws on expertise from respective disciplines to address a problem, the transdisciplinary approach is more combinatorial and seeks a synthesis—something new entirely. Transdisciplinary research consists of “efforts conducted by investigators from different disciplines working jointly to create new conceptual, theoretical, methodological, and translational innovations that integrate and move beyond discipline-specific approaches to address a common problem” (Harvard Transdisciplinary Research in Energetics and Cancer Center, 201916).

Further, transdisciplinary approaches have been used in research related to disaster risk reduction, sustainability, and adaptation to climate change. Bendito and Barrios (2016)17 highlight the importance of this approach to address the complexity of conditions that promote vulnerability and to provide integrated knowledge to support the recovery and mitigation process.

Rapid reconnaissance research collects perishable data to allow for the understanding of context, interactions, and dynamics before, during, and after a disaster (Kendra & Gregory, 201518). Disaster complexity makes it common for research teams to employ interdisciplinary approaches where scientists share knowledge (Kendra and Gregory, 2015).

The team had a range of expertise that spanned the fields of civil engineering, urban planning, geography, medical sociology, urban ecology, sustainable construction, social policy and human services management, disaster science and management, and social work. The goal was to approach the reconnaissance mission from a transdisciplinary perspective, drawing from multiple fields to assess the state of post-disaster recovery in the USVI.

The SURGE team not only integrated scholars from different disciplines, but also incorporated local actors from the USVI in an attempt to give continuity to the reconnaissance research. This field report summarizes how our transdisciplinary team engaged with ongoing recovery efforts—as well as the actors and institutions leading them—in the post-disaster context of the USVI while conducting a rapid reconnaissance mission to assess recovery needs. Local informants from the USVI became a key part of identifying recovery concerns and simultaneously collaborated to generate ideas on future recovery initiatives based on SURGE’s natural and built environment assessment.

Research Questions

The research questions that guided our rapid reconnaissance study were as follows:

What were the impacts of Hurricanes Irma and Maria on the built and natural environments in the U.S. Virgin Islands?

How are long-term recovery efforts in the U.S. Virgin Islands addressing these impacts?

In what ways did the use of a transdisciplinary team during a rapid reconnaissance study assist in identifying the impacts and long-term recovery needs in the U.S. Virgin Islands?

Methods

We conducted a transdisciplinary rapid reconnaissance study that incorporated disciplines including engineering and natural and social sciences. Through a combination of participatory observation in listening sessions with community leaders, meetings with on-site partners, and visual documentation, scholars solicited information on ongoing recovery efforts. Our team was able to gather information from key informants through formally arranged presentations, face-to-face conversations, and service-learning activities. Scholars participated in a community service activity and surveyed the visible impacts of the 2017 Hurricanes Irma and Maria in St. Thomas and St. John while in the USVI. Most listening sessions with community leaders ranged from 60 minutes to two hours, whereas visual surveying of the islands included four- to six-hour visits of St. Thomas and St. John. Throughout the rapid reconnaissance, the team gathered for reflective sessions to share lessons learned and capture initial themes and findings among the transdisciplinary team.

Figure 3. SURGE members participating in the St. Thomas Long-Term Recovery Board Meeting.

Given the diverse disciplinary background of our team, we decided to investigate the USVI hurricane impacts from the perspective of the built and natural environments. We acknowledge that these categories overlap, given the human influence on natural environments and systems. However, this ontology became a guiding mechanism for data collection and division of tasks, based on the varied expertise in our group. The two groups of built environment and natural environment were determined by different disciplines to promote the transdisciplinary perspective. Generally, those who collected data on the built environment came from urban planning, civil engineering, and social work. Similarly, those who collected data on the natural environment included team members with backgrounds in sustainable construction, urban ecology, public health, and geography.

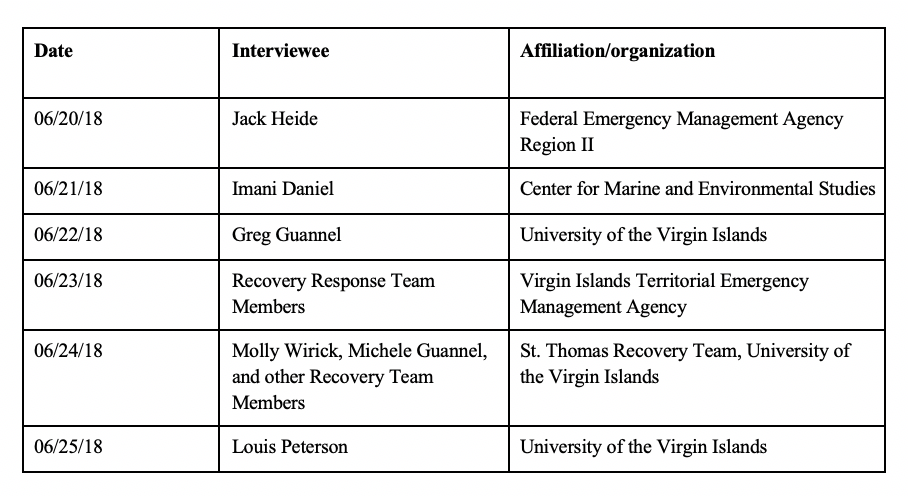

Below is a table summarizing the interviews conducted, as well as a comprehensive summary of the field visit.

Field Visit Summary (June 15-20, 2018)

Day 1: Conversation with Jack Heide, Community Planner, FEMA Region II

The arrival of the SURGE team coincided with the tail-end of the Hazard Mitigation and Resilience Workshop hosted at the University of the Virgin Islands. While most of the attendees dispersed, Kim Waddell of the University of the Virgin Islands was gracious enough to give the team a quick welcome and Jack Heide, a community planner with the Federal Emergency Management Agency Region II, sat down with the team to share his perspective on the recovery process. Heide works specifically on mitigation planning for the territory in conjunction with local agencies. One of the main concerns he expressed in this conversation was the capacity of the local government. He indicated that the same level of attention isn’t given to the needs of a territory as compared to a state in the post-disaster context, and that many local government departments were already understaffed and strained before the hurricanes. Although plans were being developed, Heide was worried about the ability to implement and manage future projects. The next two biggest issues he discussed were the maintenance and reliability of the power grid and debris management. Heide didn’t share much about potential projects for the power grid during the conversation, but he did mention that new telescoping composite telephone poles had arrived and were being erected on St. John, which might mitigate future communication issues. At the time of the conversation, debris was being exported from the island and the shipping costs were significant. Heide stated that debris from Hurricane Hugo in 1989 was still present, which brought up questions about the most effective way to remove the new debris. In addition to faith-based organizations, Heide also stated that there were long-term recovery teams on each of the islands, and each were at different points of the process of assessing recovery needs, which highlighted the challenges of serving a territory consisting of distinct communities. Finally, Heide informed us that the USVI will be receiving funding that will total about ten times the usual territory annual budget for its recovery efforts, which pointed back to the issue of local government ability to manage and allocate funds sufficiently. For example, the territory planned to adopt the 2018 International Building Code standards and had roughly $8 million to fund such an initiative, but it was unclear what the enforcement of those new standards would look like. All-in-all, the focus is on recovery and preparedness efforts and Heide said he viewed his role as supporting the local government in the efforts and projects to rebuild the islands.

Day 2: Service-Learning Activities - Marine Debris and Mangroves

Imani Daniel and colleagues at the Center for Marine and Environmental Studies19 (CMES) hosted the SURGE team on Day 2 of the reconnaissance mission for a service-learning exercise, which involved the retrieval and removal of marine debris from the beach and morphological data collection on mangrove saplings planted after Hurricanes Maria and Irma. Upon arrival of the SURGE team, the CMES group gave a brief report on the devastation the hurricanes had created on the reef, shoreline, and inland green barriers such as mangrove trees. The CMES and SURGE groups explored the shoreline and examined numerous sea animals that had washed up the shore and established new habitats after the hurricanes. The SURGE team went on a swimming excursion to search for, retrieve, and remove debris from the sea floor within 10 meters from the shoreline, as well as participating in a beach clean-up that was part of an ongoing current research project. The amount and types of debris removed from the beach shoreline and near reef made it evident that the recovery and restoration process at St. Thomas was moving slowly. The SURGE team was able to remove remaining glass and plastic bottles, tin cans, and pieces of wood, metal, and cloth.

In addition, the SURGE team was able to contribute to replanting part of a mangrove forest that had been destroyed during the hurricanes. Mangrove swamps are common ocean shoreline ecosystems that build up the shoreline and protect inland areas (including the built environment) from storm damage. Mangrove tree roots play an important role in creating and maintaining millions of ecosystems of flora and fauna; trapping mud, dirt, sand, and floating debris; and harboring fish and other ocean animals for food, predation, and shelter. This rich and strong ecosystem in turn attracts predators to stabilize food webs and build up soil. Effective green belts of mangrove trees (also called landformers) planted along the shoreline will result in soil accretion over time, allowing different species of mangrove to colonize the soil and eventually convert the area to land while the shoreline moves seaward, creating thicker green buffers.

In the USVI, a variety of mangrove species can be found living in in saltwater and brackish water wetlands. Black mangroves are found in drier areas, red mangroves in aquatic areas, and white mangroves inland in moist, sandy areas. The 2017 hurricanes destroyed most of the mangrove trees on the islands and resulted in significant inland flooding, vegetation damage, soil erosion, and sediment accumulation. This caused significant damage to the reefs and seagrass beds as sediments and anthropogenic and plant materials flowed from the land to the beach, displacing some habitats while fragmenting others. Most of the white and black mangrove species were lost and only a few of the red mangrove species remained.

As part of our service-learning exercise, the SURGE team helped with an existing mangrove restoration project by collecting sapling height, leaf count, and mortality data on white or black mangrove saplings that were planted in a limited area after the hurricanes. Urgent recovery and restoration of the mangrove trees was necessary to combat the 2018 hurricane season. This required expertise from natural, built, and social science disciplines to effectively establish strong, resilient mangrove forests.

Figure 4. Service-learning at the Center for Marine and Environmental Studies (CMES).

Day 3: Excursion to St. John

The third day of fieldwork was dedicated to visiting and better understanding the recovery of St. John. Daniel led the SURGE team on a tour of St. John. After exiting the barge at Cruz Bay, we drove into the National Park, which occupies the majority of the island. Most of the trees were stripped of their leaves or toppled over. The vegetation served as a prominent indicator of just how strong the storm winds were and the scale of the devastation. Daniel guided the team around Coral Bay, which is known for its fishing community, to see how heavily it was impacted by mangrove loss. While in Coral Bay, we were able to view composite telescoping poles that Jack Heide had mentioned were waiting to be installed. Such poles are better able to withstand hurricane-force winds and therefore make telecommunications more resilient. At the time of the visit, these poles were only being installed only on St. John.

One of the last stops on this excursion was to Trunk Bay, a popular tourist destination within the National Park. There was still vegetation debris in areas near the beach and dead mangroves nearby. Daniel noted that there were significantly less fish in the shallow waters compared to before the hurricanes hit the islands. Despite the remnants of the storms, visitors were still enjoying the beach. As the SURGE team waited for the barge back to St. Thomas, a number of informal discussions were had about the variable recoveries across the USVI. For instance, St. John, which is known for having a smaller but more affluent population, is further along the recovery process compared to St. Thomas or St. Croix. Questions arose about how a territory of three somewhat disparate communities might pool resources for a more comprehensive recovery overall.

Day 4: Hurricane Preparedness Meeting at the University of the Virgin Islands

Our team attended a presentation by the Virgin Islands Territorial Emergency Management Agency (VITEMA)20 at the University of the Virgin Islands. The presentation focused on campus-wide efforts to improve emergency management during hurricanes, as well as island-wide efforts to address recovery. VITEMA serves as the major coordinating unit for all disaster-related agencies. Following Irma and Maria, the agency had pinpointed five areas of improvement for future disaster management: communication, evacuation, points of aid distribution, training, and emergency action preparedness. Our informants noted that the coordination effort was critical in the recovery process. Bonds and Washington spoke about the lessons learned from personal preparation and highlighted VITEMA’s effort to strengthen properties by using architectural firms to assess public and private residences that might be vulnerable. The agency had also created an inventory of materials and equipment vital to evacuation processes, lengthened the number of hours before issuing hurricane warnings from 48 hours before landfall to 72 hours, and stressed the need for USVI residents to personally prepare for disasters.

Day 5: Long-Term Recovery Board Meeting, School System Seminar

On the fifth day of the reconnaissance trip, we observed one of the monthly meetings held by the STRT. The meeting was chaired by STRT Executive Director Imani Daniel. Present at the meeting were political leaders, FEMA representatives, two representatives from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and two students from the University of the Virgin Islands. Since the islands have different goals and priorities, St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix each have their own recovery team. The main aim of this group was to rebuild homes and restore the emotional and physical welfare of residents, focusing specifically on St. Thomas.

During the meeting, several topics were presented related to that goal. FEMA and the STRT Cultural and Arts Committee laid out a plan for a cultural and arts event they were collaborating on to spur community revival and provide stress relief. Since the STRT serves as a liaison between residents and NGOs, one NGO introduced a service to help insured residents who owned their homes rebuild or repair. The group also discussed the plight of tenants in the badly damaged Tutu Hi-Rise housing projects who did not want to be relocated, both because they did not want to lose their sense of community and because government financial incentives were not enough for them to find affordable housing elsewhere.

In keeping with the goal of community engagement, the SURGE group was given the opportunity to provide feedback and ask questions related to the meeting topics. SURGE scholars gave suggestions on recovery efforts that included the recycling of debris or waste to create construction materials; encouraging and improving agriculture on the island; and engaging residents and students in reconnaissance and recovery planning efforts. Attendees agreed that at least one SURGE scholar should attend future meetings via video call to further help support recovery evaluation.

After the STRT meeting, the SURGE team met with the U.S Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) staff housed in the FEMA office, including interim director Molly Wirick, who had been assigned to the USVI a few weeks earlier. She gave the team a brief history on the health system of the USVI, focused mainly on St. Thomas. She related that most of the hospitals and clinics experienced severe damage from the hurricane, so people were going to the mainland for treatment.

Wirick stated trauma and mental health was an issue that FEMA and HHS were planning to target, as they suspected that most of the islanders were dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder related to the loss of property and the deaths of family members. The department was also working on a project related to behavioral health of school children and the use of trauma-informed approaches in schools, including working directly with schools and their administration, parents, and teachers. FEMA and HHS also planned to engage with faith-based organizations to provide counseling and therapy for residents. She stated that the HHS office on the island had been shut down because of hurricane damage and rebuilding it was another project FEMA was embarking on at the time of our visit.

The SURGE team also heard a talk from two teachers—one from a public school and one from a private school—who spoke about how the school system in the USVI was functioning after the hurricane. A student also presented her account of her experiences after the hurricane and how it affected her and her classmates, some of whom had yet to recover from the trauma.

The speakers reported that they had to clean up their own classrooms and address mold that grew after the hurricane. Debris management was also a problem and some of the teachers reported that they there was still hurricane debris piled on the premises. Another issue was the limited amount of classroom space available, which created the need for students to attend school in shifts. The shifts did not provide enough time for teachers to cover the whole curriculum, especially since the students had missed the majority of the year due to the hurricane. The teachers said they devised innovative ways to make the class more interesting for the students by giving them practical assignments and involving them in model-building activities.

At the time of our reconnaissance visit, some students and teachers had not yet returned to school after being displaced by the hurricane, resulting in a shortage of teachers. The teachers who returned shared that they felt a need to set aside their own trauma and post-hurricane challenges to address the needs of their students and community. Students reported that they were also struggling with their hurricane experiences, and some had developed behavioral issues like truancy and substance abuse.

Day 6: Future Partnerships and Departure

Before departing the USVI, the SURGE team visited the University of the Virgin Islands College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Department where the team discussed the possibility of a collaborative initiative between SURGE, CMES, and the College of Agriculture to establish community-focused home gardening projects. Post-disaster, the projects could potentially alleviate food shortages, reduce dependency on food imports, and increase the islands’ overall food security. In addition, the team proposed harvesting, drying, and processing the uprooted and floating seaweed to manufacture fertilizer. The college expressed willingness to collaborate with the SURGE team and highlighted cooperative economic models that can be used to facilitate community gardening projects.

Findings

Several thematic questions and concerns arose about how the territory and its citizens will recover (economically, ecologically, socially, etc.) in the coming years. Given the wealth of information shared during the trip, the major takeaways can be organized into impacts for the natural and built environments.

Human-Built Environment Interactions

Some of the major concerns surrounding the recovery of the built environment included communications infrastructure, debris management, water management infrastructure, integrity of shelter and household structures, and governance around infrastructure.

Communications infrastructure: About 112 telecommunications towers were destroyed by the storms. Satellite phones were not functional after the storms because of cloud cover. At the time of the SURGE fieldwork, cellular coverage was still not back to 100 percent. Immediately after the storms, ham radios were used for communications when all other methods failed. Ongoing recovery efforts now involve installing telescoping, composite material telephone poles able to withstand hurricane-strength winds on St. John in order to provide more structurally sound alternatives to previously installed poles. In addition, VITEMA—realizing the impact of the communications blackout—created a new mass communication platform called Alert VI for emergency alerts, which enables emergency managers to communicate with local communities and each other across multiple platforms in the case that one fails.

Debris: There are hundreds of thousands of square feet of debris on St. Thomas, which—although only a fraction of the 1.2 million cubic yards across all three islands—remains a long-term problem for the territory during the recovery period. There is no plan for the debris, other than to remove it from the islands. There are no recycling facilities in the USVI. The approach to debris management is to have individuals take their debris to landfills, which are already so full that that they were scheduled to close in 2018, although they were originally scheduled to close in 2020. There is growing awareness among government actors, NGOs, and community leaders that this poses a long-term problem for the islands.

Water Management Infrastructure: Many communities in the USVI use cisterns, located within the foundations of many building structures on St. Thomas, to collect rainwater. This made for more resilient water management, as many people still had personal access to water for agriculture and everyday use after the hurricanes. For example, the foundation of the farmers market stand in the eastern community of Bordeaux on St. Thomas has a cistern that provides water for preparing and selling fruits and vegetables. The success of cistern use in the post-disaster context has motivated many islanders to continue using cisterns to store water in St. Thomas, as well as installing cisterns in new construction moving forward.

Shelter and Household Structures: Construction is variable, often informal, and not always resilient in the USVI. Many buildings and shelters on St. Thomas are not adequate to withstand hurricanes in their current condition, since they are not up to code. For example, the aluminum walls the Tutu Hi-Rise housing community, built in the 1970s, were not able to withstand wind damage during the hurricanes. Additionally, many shelters and homes on the island were built informally; residents do not have property rights and therefore cannot qualify for insurance and/or relief, posing a serious barrier for funding reconstruction of damaged structures during the recovery period. Another barrier to reconstruction is that of procuring construction materials. This is logistically more challenging for the USVI, as materials take longer to arrive by ocean cargo, the most cost-effective means of transporting materials to the islands. Recognizing these challenges is a first step to designing better strategies for building or retrofitting more resilient structures before the next disaster.

Governance infrastructure: The USVI local government infrastructure currently lacks sufficient human resources to deal with the aftermath and recovery of disasters. There is insufficient medical recordkeeping; many records are paper-based and were damaged during the hurricanes. This significantly slows down the process of tracking people and ensuring their wellbeing post-disaster. Also, institutional knowledge about hurricane response seemed to be varied across different sectors before and after the storms. As a result, the STRT, with support from FEMA, was established to lead and coordinate recovery efforts across the islands, as well as across sectors.

Figure 5. Accumulation of debris in St. Thomas.

Human-Natural Environment Interactions

Some of the major concerns surrounding the recovery of the natural environment included the destruction of mangroves, increasing algal blooms, restoration of vegetation, management of non-native invasive species, and food insecurity.

Mangroves: More than 70 percent of coastal mangroves were lost or damaged in the 2017 hurricanes. These mangroves provide a nursery for fish and marine life and a barrier for boats and heavy coastal winds, waves, and floods. The depletion of the mangroves contributed to increased glass and plastic water bottles, metals, wood, and sediment in the ocean. In addition, destruction of the mangroves has had a direct economic impact on subsistence fishing and the fishing industry at large. Moreover, loss of mangroves significantly disturbed marine ecosystems and ecological stability.

Algal Blooms: Increased algal blooming was observed post-hurricanes, possibly due to excess phosphorus and nitrogen runoff during soil erosion (sediment runoffs) and destruction of the mangrove barrier. The presence of algal blooming indicated external nutrient input from point sources, such as sewage discharge and animal feeding operations, and nonpoint sources, such as diffuse runoff from agricultural fields, roads, and storm water. Increased algal growth depletes dissolved oxygen and nutrients (e.g., phosphorus) and blocks sunlight from reaching plants at the seabed, impacting aquatic life forms and ecosystem stability and resilience. The mangrove monitoring and restoration project at CMES is a great start toward regaining some of these lost ecosystem services, but more assistance will be needed for scaling up such efforts, as well as for providing long-term support to ensure successful establishment of the young mangroves.

Restoration of Vegetation: Significant damage was done to the native vegetation, which aids in breaking heavy winds, providing shelter and food, holding soil and water, and lessening the impacts of hurricanes and floods. Tree losses reflect the ability of eroded and nutrient-deficient soil to strongly anchor trees. There is great opportunity to also re-establish some of the impacted natural areas, but it was unclear if there were any ongoing efforts.

Non-Native Invasive Species: An increased occurrence in non-native lionfish and non-native seagrass were noted post-hurricanes. Non-native species negatively impact the native flora and fauna population, local species composition, habitats, and marine food webs (ecological cascade). There is the possibility of a decline in local fish catch and supply across the islands due to increased predatory fish and destruction of fish habitats. The non-native seagrass has invaded, decreasing the native seagrass population and fragmenting the aquatic plant community composition. The impact of non-native species invasion on aquatic life in St. Thomas is currently an area of focus for scientists at CMES. Native seagrasses form a crucial part of the reef flora and fauna communities, which also impact local fishing and human livelihood and well-being.

Food Insecurity: More than 95 percent of the islands’ foods are imported from the U.S. mainland, and food insecurity remains a great threat to the island pre- and post-disaster. It was shared that agriculture, as an industry, had fallen out of favor culturally. There are also physical challenges of drought due to topography (e.g., slopes) and the extensive built environment (e.g., reducing precipitation, infiltration, and percolation). Few home gardening projects exist, but developing home gardens could alleviate food shortages and scarcity post-hurricanes, decrease food import volumes, and increase economic self-sufficiency. Moreover, there is no robust recycling/green programs that could contribute to improved local soil quality. For instance, post-hurricane debris, such as plant materials or uprooted seaweed, could be used to make organic fertilizer, and concrete rubble could be used to amend calcium-deficient soils and construct retaining walls for home garden beds and hillside farming.

Figure 6. Accumulation seaweed in shoreline could be used to make organic fertilizer.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. First, the timeframe of the study (five days) resulted in data that represent only a narrow snapshot of recovery in the USVI. We have mitigated this limitation by assigning two SURGE team representatives to liaise on a monthly basis with the STRT to stay apprised of ongoing recovery projects and efforts. Second, the scope of interviews was based on our pre-existing connections in the USVI, mainly through the University of the Virgin Islands. The majority of our interviewees are practitioners, and we lack the perspective of community members on their experience of the hurricanes. Finally, our choice to organize research questions and findings between built and natural systems is limiting in the sense that it takes focus away from human systems, which cut across both categories. This is a result of not having sufficient interviews and data about community member experiences of the hurricanes and can be the focus of future follow-up work.

Lessons Learned and Future Work

Moving forward, the SURGE Scholars have set goals for the next year of the program. The scholars plan to build a team project that intersects with issues of both the natural and built environments of the USVI, as well as take advantage of this transdisciplinary approach, allowing all scholars to contribute their expertise. These goals are:

To revisit the USVI in 2019 with a new SURGE cohort and continue service-learning opportunities for future missions, including adding a visit to St. Croix.

To develop a collaborative project together with University of the Virgin Islands partners (faculty, staff, students, and the greater community). It is important to the mission to foster a project with input from the community, which can start with the university and extend outward.

To maintain a partnership and advisory role aimed at providing support, technical expertise, and assistance to the STRT to best meet the needs of the communities that they serve. The scholars can shape the SURGE program model by providing the information and tools to empower the local community to recover and thrive in their own unique way.

At the time of writing, the SURGE team has also developed a collaborative project proposal with the University of the Virgin Islands and local government representatives centered on urban agriculture as part of the recovery process in addressing food security.

Acknowledgements. This SURGE team would like to extend a special thanks to the St. Thomas Recovery Team, University of the Virgin Islands EPSCOR program, and Jamile Kitnurse (District Sales Manager at PepsiCo) for their support in the field work for this report. These findings were also shared at the poster session during the 43rd annual Natural Hazards Research and Applications Workshop in Broomfield, CO.

The data collected for this report was funded by the National Science Foundation, NSF INCLUDES: Minority Scholars from Underrepresented Groups in Engineering and Social Science Building Capacity in Disasters (NSF Award #1744479).

References

-

Virgin Islands Housing Finance Authority. (2015). U.S. Virgin Islands 2015-2019 consolidated plan for housing & community development. Retrieved from https://www.vihfa.gov/sites/default/files/reports/VI%20Consolidated%20Plan%20%26%20Annual%20Plan%20draft%207-8-15.pdf. ↩

-

Moorhead, Justin. (2018). Op-ed: Population, demographics, and migration. The Virgin Islands Consortium. Retrieved from https://viconsortium.com/opinion/op-ed-population-demographics-and-migration/. ↩

-

Potter, R. B. (2017). The urban Caribbean in an era of global change. Routledge. ↩

-

Kossler, B. (2017). The V.I. budget crisis: Part 2, The Hovensa effect. The St. Croix Source. Retrieved from https://stcroixsource.com/2017/04/16/the-v-i-budget-crisis-part-2-the-hovensa-effect/. ↩

-

Sattler, D. N., Preston, A. J., Kaiser, C. F., Olivera, V. E., Valdez, J., & Schlueter, S. (2002). Hurricane Georges: A cross-national study examining preparedness, resource loss, and psychological distress in the US Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, and the United States. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15(5), 339-350. ↩

-

Hubbard, D. K. (1992). Hurricane-induced sediment transport in open-shelf tropical systems; an example from St. Croix, US Virgin Islands. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 62(6), 946-960. ↩

-

National Hurricane Center. (2017). Atlantic hurricane season reports. Retrieved from https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/index.php?season=2017. ↩

-

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Centers for Environmental Information. (2019). State Climate Summaries: Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Retrieved from https://statesummaries.ncics.org/pr. ↩

-

Smith, N. (2006). There’s no such thing as a natural disaster. From Understanding Katrina, perspectives from the social sciences series. Social Science Research Council. Available at: http://understandingkatrina.ssrc.org/Smith. ↩

-

Squires, G., & Hartman, C. (2013). There is no such thing as a natural disaster: Race, class, and Hurricane Katrina. Abingdon: Routledge. ↩

-

Kelman, I., & West, J. J. (2009). Climate change and small island developing states: A critical review. Ecological and Environmental Anthropology, 5(1), 1-16. ↩

-

Atsumi, T., Seki, Y., & Yamaguchi, H. (2018). The generative power of metaphor: Long‐term action research on disaster recovery in a small Japanese village. Disasters, 43(2), 355-371. ↩

-

St. Thomas Recovery Team (STRT). (2019). Retrieved from https://strtvi.org. Accessed 27 February 2019. ↩

-

Hadorn, G. H. (2008). The emergence of transdisciplinarity as a form of research. In Handbook of transdisciplinary research (pp. 19-39). Eds. Hadorn, G.H., Biber-Klemm, S., Grossenbacher-Mansuy, W., Hoffmann-Riem, H., Joye, D., Pohl, C., & Zemp, E. Dordrecht: Springer. ↩

-

McGregor, S. L. (2004). The nature of transdisciplinary research and practice. Kappa Omicron Nu Human Sciences Working Paper Series. Available at: http://www.kon.org/hswp/archive/transdiscipl.pdf. ↩

-

Harvard Transdisciplinary Research in Energetics and Cancer Center. (2019). Definitions. Retrieved February 27, 2019, from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/trec/about-us/definitions/. ↩

-

Bendito, A. & Barrios, E. (2016). Convergent agency: Encouraging transdisciplinary approaches for effective climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 7, 430-435. doi:10.1007/s13753-016-0102-9. ↩

-

Kendra, J. & Gregory S. (2015). Final project report #60: Workshop on deploying post-disaster quick-response reconnaissance teams: Methods, strategies and needs. Retrieved from https://udspace.udel.edu/bitstream/handle/19716/17479/DRC%20Final%20Project%20Report%20No%2060.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y ↩

-

Center for Marine and Environmental Studies (CMES). (2019). Retrieved from https://www.uvi.edu/research/center-for-marine-environmental-studies/default.aspx. Accessed 27 February 2019. ↩

-

Virgin Islands Territorial Emergency Management Agency (VITEMA). (2019). Retrieved from https://vitema.vi.gov. Accessed 27 February 2019. ↩

Adegoke, M., Bui, L., Commodore-Mensah, M., Derakhshan, S., Higgs, I., Lane Filali, R., McDermot, C., Nibbs, F., Álvarez Rosario, G., & Sylman, S. (2019). The SURGE Experience: A Service-Learning Approach to Assessing Disaster Recovery in the U.S. Virgin Islands (Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, Report 292). Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/the-surge-experience